I see patterns. Fear not, this isn’t the introduction to a new M. Night Shyamalan movie but I do enjoy opportunities where I can connect the dots. Maybe it is the linear, logical, left –brain, former programmer in me but I relish when I find patterns that emerge across different disciplines, groups, organizations, etc. Five years ago I was part of a public policy group that mixed professionals from different worlds – for-profit, nonprofit, government, education, etc. The goal of the program was to advance public policy awareness and build public policy leadership. What I quickly recognized was that many of the same issues that were challenging me in the “for-profit innovation arena” were also plaguing these other groups. The challenges of funding, personal & organizational risk, managing expectations, and the fear or failure were consistent. There were some nuances but there was far more similarity that difference.

This article is my first in a three part series specifically focused on Driving Nonprofit Innovation. I’ve broken it into three pieces to make it easier to digest: 1) Managing the Process from Idea to Launch, 2) The Challenges of Funding Nonprofit Innovation, and 3) Building the Culture & Skills for Sustained Innovation.

This article is my first in a three part series specifically focused on Driving Nonprofit Innovation. I’ve broken it into three pieces to make it easier to digest: 1) Managing the Process from Idea to Launch, 2) The Challenges of Funding Nonprofit Innovation, and 3) Building the Culture & Skills for Sustained Innovation.

During discussions with nonprofit leaders the first concern with innovation programs is always how to manage the process: too many ideas, too few people, too little time, and too much risk. This is what I have learned.

Starting the innovation journey

Most nonprofit leaders have new ideas flooding in all of the time. How they might improve their organization, expand their services, and expand their reach. These ideas come from every group of stakeholders: board members, funders, employees and clients. The challenge for most nonprofit organizations is not a shortage of ideas but a shortage of resources. This is the identical problem that for-profit startups have. Where will the money come and who will lead and support each of these great ideas?

Sorting through of the opportunities is usually the first challenge. Which will provide the best material benefit to the organization but not consume too many resources? Being able to answering this question is necessary for defining an innovation strategy for your organization; a process that will take effort, patience, and focus.

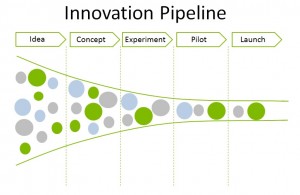

A first step should review your organization’s mission, vision and values. These elements will be important factors when weighting out which initiatives you will focus on and which priority of sequence. One of the next tools that I encourage organizations to consider is building a frame work for an Innovation Pipeline. The stages of a pipeline can be unique for the organization but should have a sequence of filters and gates that will help guide the team in making decisions and tracking ideas as they move toward execution.

An example that I use with retail organizations has five phases to a pipeline: 1) idea, 2) concept, 3) experiment, 4) pilot, and 5) launch.

An Innovation Pipeline as a tool

The pipeline moves from left to right. Ideas should enter the funnel and be captured from all of the stakeholder groups previously mentioned. The next step requires support from a group that can continually help compare and contrast those ideas against the mission, vision, and values. The ideas that rank well should be prioritized and move into concept phase. During the concept phase there will need to be some effort put to quantifying the idea. Ideas should be measured for their potential impact, possible drain on resources, likelihood of success, impact of not taking action, and risk to the organization. The goal is not to be 100% accurate with your calculations but with a degree of uncertainty that you and the organization are comfortable with.

The pipeline moves from left to right. Ideas should enter the funnel and be captured from all of the stakeholder groups previously mentioned. The next step requires support from a group that can continually help compare and contrast those ideas against the mission, vision, and values. The ideas that rank well should be prioritized and move into concept phase. During the concept phase there will need to be some effort put to quantifying the idea. Ideas should be measured for their potential impact, possible drain on resources, likelihood of success, impact of not taking action, and risk to the organization. The goal is not to be 100% accurate with your calculations but with a degree of uncertainty that you and the organization are comfortable with.

This is a good place to discuss the unique difference between Incremental vs Disruptive innovation initiatives. Incremental initiatives usually involve less unknown elements. They take an original product or service and build on it or change it slightly. With less unknown elements there is a lower risk of failure when launching the initiative. These ideas can more easily be tested and corrections can be made along the way. Disruptive innovation usually involves a higher degree of unknown elements and thus a higher risk of failure.

One way to reduce the risk of failure in either type of innovation is by running the concepts through an experiment phase. Is it possible to validate the hypothesis in a smaller test prior to committing the full amount of resources that would be required to launch such an initiative? The experimentation phase should be iterative – testing and retesting different variations of the hypothesis.

Once you have found pieces that work through the experimentation phase you can bring them together in a pilot program where you are testing something that will more closely resemble the final product or service. Similarly, the pilot phase is also an iterative process and sometimes will require running new experiments. A pilot is meant to give you “real world” feedback on your initiative before you roll out the final version.

The process culminates with the Launch (or Scale) phase. A couple of noteworthy points here based on experience and research – most ideas will not make it to the launch phase. According to a Fahrenheit 212 (a NYC based innovation consultancy) survey of 100 Chief Innovation Officers fewer than 25% of their innovation initiatives ever see the light of day. Most new ideas do not work out along the way. This is the simple reality of innovation work – new ideas require a level of risk taking. How much risk your organization can take or should take depends greatly on the organization. An example I often give is that most grocery stores operate on 3% gross margins and 1% net margins. Those thin margins leave grocers with very little room for error when trying out new ideas with their business. The good news is that they can run experiments easily with real customers every day and unlike social service nonprofits a failed experiment is not going to negatively impact someone’s life. If their failures can be quick and cheap they can minimize their impact.

Not perfection but a process

The intent of the Innovation Pipeline is not perfection but as a tool to help you manage the processes involved, develop criteria and measurement standards, funnel resources to priority projects, halt or end non-priority projects, and to reinforce an iterative process. Getting a project from idea to experiment is a success. Deciding not to go forward based on experiment results does not mean failure. Instead it means successfully freeing up those resources to work on another higher priority project. Maybe circumstances will change to your favor in the future and suggest that you retry that initiative but you cannot spread your resources too thin or you’ll be certain to find an abundance of failure.

Food for thought:

(image source: Huffington Post)

Receive periodic email updates from Matt Hunt including his published pieces, updates on his progress, and more!