Learning from Failure… a collection of stories, insights and lessons learned.

We hear it so often that it has become cliché. Small companies are nimble and move quickly where as large companies can muster significant resources but are slow to respond to emerging threats and opportunities. In response to their admitted slow pace many big companies have focused their attention on acquisitions as a way to mitigate threats and infuse new growth opportunities into their business.

[This post is a reprint of my article that was originally published on October 23rd, 2014 in Innovation Excellence.]

According to Clay Christensen and his team at Harvard (The Big Idea: The New M&A Playbook) – companies spend more than $2 trillion on acquisitions annually. With research showing the failure rate of mergers and acquisitions between 70% and 90% the best case scenario is that we are wasting $1.4 trillion per year on failed acquisitions.

The question then becomes “why is it that so many of these acquisitions fail to deliver the expected benefit for the acquiring company?” Are the acquiring companies imposing their slow pace and risk mitigation policies onto the smaller company? In 2002, consumer electronics giant Best Buy was looking to fuel their growth into PC, home theater, and appliance services. To jump start that work Best Buy acquired the then startup Geek Squad which had been founded by entrepreneur Robert Stephens in 1994. During our recent interview Robert shared his story of entrepreneurship, risk taking, acquisition strategies, his pick for Most Visionary CEO, and an expensive 99 cent burrito.

In 2000 when I called on Best Buy we were in four cities: Minneapolis, Chicago, San Francisco, & Los Angeles. We didn’t have any offices. Literally we didn’t have any offices. Just cars and people and we dispatched everything out of Minneapolis.

Our model was kind of like Uber is today. We didn’t have a lot of infrastructure – we just had people, cars and dispatch.

I’m risk averse. I don’t take risks. There are risks that you know you’re taking and the ones you don’t. At the time my risk was staying in school and taking on more debt. That was the risk I was avoiding by starting my company. I didn’t think I could work anywhere in a big corporation so I was forced to found a company. I didn’t wake up deciding to be an entrepreneur – I just didn’t see any other options.

The truth is that I applied to become Prince’s head engineer but he didn’t hire me. Had Prince hired me I would have toured the world and had fun parties but I would have never started my company. There is a reason that you start a company in your 20’s before you have kids and settle down. You have less risk.

Like for me my youngest is 16 years old so in two years I will have reduced my risk again. I will go back to having 20 hours a day free, no kids at home, and under the age of 50. This means with the current progress of medical technology I will have 40 years of work ahead. Now I am more experienced. With my next startup I will be even more dangerous.

I don’t want to own anything. I do that because I am extremely risk averse. I don’t want to be encumbered by debt and that dates back to being a college student. I once bounced a check for a 99 cent burrito. I knew that I was going to bounce the check but I hadn’t eaten in a day and I was really hungry. As I watched the burrito cook in the microwave I remember knowing that this burrito was going to cost me $23. That was a really expensive burrito!

I never really got over that sense that I was that close to starvation. Which is good – it keeps you hungry and keeps you on your toes.

In terms of risk the whole deal with Best Buy is that I had no other choice. I couldn’t franchise Geek Squad. Proof of that is today. How many Geek Squads are there? None – why is that? It is a hard business that doesn’t really scale. You can barely franchise burgers and doughnuts let alone franchising a complex in-home service. The fact that there are no other “Geek Squads” is my proof that I made the right decision.

I felt I had no choice and that I had to sell Geek Squad because for me the risk was that I didn’t want my first startup to be a failure. By putting it inside of Best Buy I was able to ensure its survival. I might have made more money taking it public but I felt that I would have been ripping off my shareholders by selling them a company that wasn’t scalable. I cheated because now Geek Squad is scalable as part of Best Buy.

It was a huge change – you can’t keep beer in your office. There are two kinds of risk – those of action or inaction. There is the risk of losing the culture – startups are great and they can be innovative and drink beer at night but they lack scale and leverage. Large corporations have resources and market share that they can deploy, use, and influence but they tend to lack agility.

My risk also was staying small. I didn’t want to stay a small fry, some little computer repair person like everyone else in the yellow pages. So I traded one risk for another – and that is really how everything goes in life. You have to be honest and aware of the risks. Where people get in trouble is where they fool themselves and lie to themselves about what the risks are.

We give founders way to much credit. When you are 24 and you’re eating Ramon Noodle and 99 cent burritos that’s not really a risk you are taking. It was either that or taking on $100,000 in college debt. Now that is risky – toiling away for decades to pay off of that debt. Now that is risky. I will tell you what I am impressed with a 30, 35, or 40 year old parent who has kids and family obligations and a spouse to love and pay attention to and then decides to start a company. That is ballsy, that is gutsy, that is a person that I respect.

I don’t see many examples of good in this space. The best acquisition that I can think of is YouTube when they got acquired for $1.2 billion. Everybody thought that was insane. Now it looks like an incredibly good deal. It is very profitable. Goggle didn’t touch it, they didn’t mess with it.

If you buy a business, first of all, get over the idea that you’re going to incorporate it into your business. Whatever. That’s not really going to happen. It is better to let it live on its own because if it was hitting some growth rate you should just let it happen and not ruin the momentum.

My advice to founders is unless you are planning on staying you need to know what you are going to do next and don’t kid yourself. What I would say is that for me going forward I am only interested in working for visionary CEOs. And there are very few of them, like a handful in the world. That’s the biggest problem in corporations – they lack vision.

There is the whole size issue and can big corporations innovate but I would argue that the fish stinks from the head down. It comes down to the CEO – if your CEO does not get it your doomed. The second most important thing is the board [of directors]. For example, more than half of Amazon’s board is digital and has real expertise. I don’t know anybody from Best Buy’s board in the last ten years that had any digital expertise.

The reason that is important is that the board is the one to review the big strategic plans but if they don’t understand digital or they don’t understand trends then they can’t really evaluate it. I don’t care if they have an MBA from Harvard – there is so much disruptive technology going on that you have to know what you are talking about.

I think the most interesting and fun CEO in the world right now is John Legere (@JohnLegre) of T-Mobile US. I love his style – he is super irreverent and breaks rules. He was the fourth place carrier at T-Mobile and what is the first thing he did. He said that cell phone plans were insane and too complicated. He simplified them. That is something that any of us can do. The best CEOs simplify things – they simplify their offers. They don’t try to use trickery and fine print. You can tell his enthusiasm and he’s also made some smart moves. He is growing market share. They are still small and they have some coverage issues but I think he has done the best he can with the hand that he was dealt.

In January, he was in Las Vegas for the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) and showed up at AT&T’s party. He loves Macklemore and showed up for the concert and they kicked him out. AT&T played it just like David vs. Goliath and Legere played it masterfully.

So he uses Twitter, he’s a CEO who is really on social media. I don’t even think that a company should have a social media team anymore. That was fine when Twitter and Facebook came out but the problem is that when a company has a social media team – nobody else in the company needs to be on social media.

I want the CEO to be on social media – I want the CEO personally tweeting. You can have legal and marketing departments on Twitter but the CEO needs to be there and available.

As Robert stated above, sometimes the risk isn’t in starting your own company but in taking on college debt with the uncertainty in how you will repay it. For Robert and Geek Squad it was imperative to partner with a company like Best Buy that could scale complex in-home services across the country. He recognized that would mean slower decision making and more politics but he saw it as the lesser of two evils which was remaining the “small fry.”

Robert has a good understanding of his own risk tolerance is looking forward to returning to entrepreneurship soon. With his further experience and understanding he expects to be even more edgy in his future endeavors. Robert follows his own advice and is incredibly active with the Twitter community. You can follow him or engage him in discussion at @RStephens.

Those that know Robert can attest that he never has a shortage of opinions. With his permission I have edited our interview for brevity and a few explicit remarks. If you’re interested you can watch our entire Skype interview available on my YouTube Channel.

Most startups will fail. Everyone in the startup community knows that failure is a more common occurrence than success. Silicon Valley has become so enamored by the “value of failure” that rumors suggest they are considering handing out merit badges for failed entrepreneurs. Just how common is startup failure? Harvard researcher Shikhar Ghosh cites that 75% of VC funded startups fail to return a single dime to their investors. So why do we hear so little about failed startups in Minnesota? Are we too “Minnesota nice” to brag about our failures?

Since 2009, former Minneapolis native Cass Phillipps has been hosting the FailCon conference in San Francisco, CA. FailCon is a daylong event focused on entrepreneurs and the startup community sharing their stories of failure and the lessons learned. The tagline for the event is “Stop being afraid of failure and start embracing it.” In my opinion we need to bring a little of that attitude back home to Minnesota?

In the last decade of my professional career I focused on driving high risk innovation initiatives and through those experiences I have learned to become comfortable with failure. I have seen firsthand the benefits of learning from my failures and those of others. I have seen the confidence rebound for individuals and teams when they realize that they have survived from a failure. My goal in sharing these stories is to help build a stronger entrepreneurial community by learning these lessons together.

Local entrepreneur Jon Wittmayer learned many lessons over the last few years and is willing to share his story of shutting down his application startup inSphere. This is Jon’s story:

[A condensed version of the following interview was originally published on

September 11, 2014 in TECHdotMN.]

1. You’ve mentioned before that the idea for inSphere came from your personal experience. What was the manifestation for inSphere?

Often when individuals find themselves in a job transition they are seeking to quickly expand their personal network with as many introductions as possible. They are hoping for quick outcomes with an introduction, a forwarded job opening, or a referral to a potential employer. This rarely happens.

It isn’t until people start building a deeper relationship that this type of support occurs.

inSphere was developed to help people build these deeper relationships. I described it as “CRM” for an individual’s professional relationships. I now see the term PRM “Personal Relationship Management” being used a lot.

When I found myself in transition I was meeting between 10 – 15 people a week. I could hardly keep up remembering anything about them. I turned to others in the same situation and what I heard was that were using Excel spreadsheets to manage their relationship network.

Having come from a business that developed SaaS based solutions I was surprised to see there was no one else working on this problem?

2. Once you identified the idea, how did you go about getting things started?

Honestly, I thought about the idea for a long time. I wasn’t sure if it was good enough to actually be a business or if I was just solving a problem for myself. I started to talk about this in my networking circles. I received positive feedback. People would say “I need something like that” or “when is it going to be available?” From there I took pen to paper and started to define how it might work, what it would look like, etc. I then bounced the idea off of a focus group and things just started to roll along.

3. Did you find it challenging as a non-technical founder of a technology company?

This is a really good question and one of the reasons I moved to close the business. I recognized early on that having a technical co-founder was important but I didn’t take action early enough. When I did start to look I didn’t realized how difficult it would be to find someone with the technical skills and the same level of passion.

Having a technical co-founder on a project is extremely important. With a technical co-founder you can stop and change directions at a moment’s notice. This allows you to be much more responsive to quick learning, customer input, and changing market conditions. It’s also the difference between spending cash out of pocket and doing it in-house for sweat equity.

4. Not having been an entrepreneur before, were you able to network with other entrepreneurs?

The Twin Cities has a tremendous support network for entrepreneurs; there are meet-up groups, organizations whose sole purpose is to help entrepreneurs. While I tapped into this a bit late it was a great help as I was getting going.

5. You have mentioned before that you appreciated Eric Ries’ book The Lean Startup. What did you find most helpful in your journey?

Eric talks a lot in his book about “Build, Measure, Learn” which, as a mantra, is really helpful to an entrepreneur. What I take from that is don’t over build and find out it’s not what your customers want. Build a little, build it quick and test to see if it’s what your customers are looking for. Fail fast, fail early and keep failing until you hit on something that is right and you can develop further and market. I didn’t do enough of this.

Along the way I also came across “Who is your customer, what problem are you solving, and what solution will you deliver?” I’m not sure if this is an Eric Ries concept but it certainly permeates the learn philosophy, and should be a guiding principle for anyone who is thinking about starting something new.

6. In 2013, the professional networking site LinkedIn added “relationship tracking” functionality to their site. Did you see this as a direct threat?

While I was working on inSphere I mostly focused on what I was doing. I was trying to get my offering right by building something to meet the needs of my users.

At the time LinkedIn had significant scale with close to 200M users, they had completed their IPO so they were flush with cash, and they were the de-facto professional networking tool – they were the 800 pound gorilla.

While their functionality was still just a fraction of what I was trying to create, I knew they could easily own relationship management.

7. Before you decided to shutdown inSphere operations you mentioned that you were putting the company on a timeline. Can you explain more?

I had my product in the marketplace for about 18 months. Somewhere around the 12-month time frame I was getting the inkling that it might not be working. The primary measure I was fixated on was the number of users and paying users.

At the time I was not focused on the product since I was receiving positive feedback every time I demonstrated it to potential users.

Instead I was focused on marketing efforts. Feeling as though I could (or should) do more. So I put myself on a 3-month timeline, with an additional 3 months if I could show significant progress. Really what I was doing was trying to hold myself accountable to the business.

8. How difficult was it for you to make the final decision to shut down the business?

It was really rather easy – easy and relieving. I stepped back, as unbiased as I could, took a look at the state of the business. Where we were today and what efforts had we tried. I assessed what could be done differently to keep the business going. In the end it was easier to discontinue the business rather than try and move forward in a new direction.

9. Looking back, are there any things that would you have done differently?

First of all I would have preferred to have a technical co-founder from day one. It is so much easier to make changes, pivot, and be agile when your development team is also a founder.

Also, I would not have sacrificed the cost of development for speed to market. I would have staged the development much more so that we could have gotten parts of the product into the hands of beta users much sooner. Momentum was lost from when I first introduced the concept to potential users and when we finally rolled out a product.

10.From your vantage point, how supportive is the local venture / entrepreneur community with failed startups?

I don’t think it is. Of course everyone wants to speak of the success story but given the failure rate of start-ups today, we should be more willing to share our stories.

I have learned so much along the way from others, I would think that someone else might be able to learn from what I did or should have done.

Just this year at MinneBar I sat in on a presentation where someone talked about his failed start-up. It was the first time I had heard someone honestly pour their heart out in an open forum. The room was packed and there were many questions for this person. I think the community is clamoring for more of these types of debriefs.

11. Do you have any advice for those that are thinking now about starting their own company?

Yes, do it! You will never regret it regardless of how it turns out. Also, talk to a lot of other entrepreneurs. Learn from what they did, didn’t do, and what they would do differently.

12. What are some things that you learned from the experience?

Being Humble – You have to be willing to do it all. Especially if you’re a solo entrepreneur you have to be willing to take on all aspects of the business. You have to learn things you never expected you might have to learn and to manage tasks you don’t particularly care to.

Highs & Lows – There is tremendous satisfaction is seeing your vision take life and to actually see people using it. On the flip side of that you also can experience the low of the lows when something isn’t going the way you had planned. But through all that you come back the next day and continue on because you still have confidence in what you’re doing.

Generosity of Others – I was amazed that so many people were willing to give their time to help me be successful. They were willing to speak the honest truth, tell you their stories, and pour their hearts out to you. This was extremely important in the early days.

Team Effort – It takes more than one person to move your idea forward whether you have employees, contractors, or friends willing to lend a hand. Recognize those people along the way and make sure they understand how important they are to you.

—

Jon was right on his opportunity identification but missed the mark on execution. There is an absolute need for tools like inSphere to help individuals move beyond personal connection “transactions” to building professional relationships.

Earlier this year I was introduced to Chuck Feltz, a former CEO at Deluxe and now an executive recruiter with Korn Ferry. A great insight that Chuck had shared with me is that in all of the people he meets as an executive recruiter fewer than 10% follow up with him after the initial introduction. They are seeing the introduction as a transaction rather than an opportunity to build a long term relationship. Chuck didn’t have a job for them at that time so they decide to move on.

As Jon mentioned, LinkedIn has added some of this relationship management functionality but the tool set available for users to manage this information is sparse to say the least. Maybe this is an opportunity for another Minnesota entrepreneur to move the idea forward? If you have any questions for Jon or just want to reach out you can connect with him via LinkedIn at Jon Wittmayer.

If you would be willing to share the story and lessons learned from your failed startup in a future issue of TECHdotMN or if you know of a good failure story that we should track down please contact me via email at matt.hunt@stanfordgriggs.com or on LinkedIn at Matt Hunt.

From childhood we are taught about the importance of perseverance. We are told that in the face of adversity we are supposed to hold firm and to strive on. The truth is that this advice is easy to give but extremely difficult to put into practice. When we are faced with setbacks or failure we naturally question our approach, our abilities, and our determination. We know that most great success stories show the hero or heroine exiting from their experience stronger than they went in but we always question our own resolve.

Earlier this year I had the opportunity to hear the story of one such heroine, DeAnna Cummings. DeAnna is the Executive Director of Juxtaposition Arts, a community based arts non-profit in North Minneapolis.

Motivated by some early successes DeAnna and her team wanted a new building to house their programs. A building that would be an arts landmark in the neighborhood. After preparing their plan and putting the ball in motion they quickly realized that the capital campaign was failing to gain traction. The setback forced them to question their approach, their abilities, and their determination.

[This article was originally published on September 1st, 2014 in the online publication Pollen]

Have you ever been told that you can’t or shouldn’t do something? How did you respond? Did you accept the feedback and choose to fold, or did you double down in your determination to accomplish that very task? Often in great success stories there is a leader who chose to persevere. A few months ago I was introduced to just such a person. In the face of harsh criticism and a failed capital campaign, Juxtaposition Arts was confronted with the decision to maintain its status quo or push forward to find a new solution.

DeAnna Cummings, the executive director of Juxtaposition Arts, shared her story of setback and perseverance during a panel discussion at this year’s BushCONNECT event. She spoke with two other nonprofit executive directors on the role of failure in driving innovation (see event video). While each of their stories was unique, a common thread ran through all three organizations: They each saw occasional failure or setbacks as part of the process of innovating, and through that innovation they want to do better work – work that is relevant to the lives of their constituents and communities.

DeAnna Cummings, the executive director of Juxtaposition Arts, shared her story of setback and perseverance during a panel discussion at this year’s BushCONNECT event. She spoke with two other nonprofit executive directors on the role of failure in driving innovation (see event video). While each of their stories was unique, a common thread ran through all three organizations: They each saw occasional failure or setbacks as part of the process of innovating, and through that innovation they want to do better work – work that is relevant to the lives of their constituents and communities.

DeAnna used the setback as an opportunity to examine her organization’s communications and her leadership style. It was also gave her a chance to reevaluate Juxtaposition’s goal around its capital campaign.

Now four years later DeAnna and her team have surpassed nearly every goal they’ve set and put previous setbacks behind them. This is the story of how DeAnna and Juxtaposition Arts (JXTA) built a sustainable model for youth arts programming, and in the process strengthened their north Minneapolis community.

Q1. You’ve said there was little opportunity for aspiring artists in north Minneapolis when you started JXTA. Can you describe the scene back then?

There were few organizations providing year-round opportunities for comprehensive engagement in the arts for youth. In the 1990s when we started JXTA, after-school programs were starting to proliferate. People started realizing that the after-school hours were when young people were most likely to get into trouble. In response, lots of programs sprung up to keep kids busy and out of trouble. Most of these programs were the traditional tutoring classes — reading, writing, and math.

Q2. The great line from the movie Field of Dreams is, “If you build it, they will come.” You barely finished building the first JXTA location and the community turnout forced you to immediately think about how to expand. What services helped you and your team make that first connection?

We’ve been in three physical locations since our founding, and each time the space was a major factor in determining what programming could be offered. In our first location we had 2,500 square feet of open warehouse studio space with high ceilings and an open floor plan. This space was perfectly suited to provide a comprehensive study and practice in fine arts. Our early program included four core components that we still use to frame our programs today:

We are still the only organization in the Twin Cities (that we know of) that offers year-round visual arts programming for young people as a pathway toward higher education and professional development. Our community members, specifically the young people, really embraced JXTA as they saw the results: young people graduating high school, going on to college, starting their own businesses, and being active, civically engaged adults. Ultimately it was word of mouth from participants, parents, partners, and investors that really helped propel the program forward in the early days.

Q3. Your capital campaign to expand and redevelop your Emerson and West Broadway building failed almost before it started. Can you share your original plans and what happened?

Q3. Your capital campaign to expand and redevelop your Emerson and West Broadway building failed almost before it started. Can you share your original plans and what happened?

When we acquired our main building at corner of Emerson and West Broadway in 2001 we purchased four buildings at the same time. Our initial plan was to focus on one space at a time. We wanted to open up our gallery, workspace, and offices first, and then immediately move to rehab the other properties one at a time. We were successful in raising the money necessary to rehab the Emerson studio and our programming quickly expanded to fill the new space.

To accommodate the growth we expanded to year-round programming. This required bringing on more artists and staff, so our budget grew. But our first space was too small, and we found that continually turning the space over from an art studio, to a board meeting room, and then to prep for a funder site visit was incredibly time consuming.

We started working with an architect and consultants on a feasibility study for rehabbing our other buildings. The plan included the designs for the renovated buildings, the programs that would be offered, and the fundraising that would be required.

Part of the feasibility study included talking to current and potential investors about our plans. The consultant found that some funders had serious questions about JXTA’s need to have more space and our ability to raise the kind of money we needed to do the level of campaign we proposed.

It became clear to me that nobody really cared about the fact that JXTA needed more space. What they wanted to hear about was what our youth, artists, and community needed, and how JXTA was going to meet those needs and opportunities. Ultimately the work isn’t about JXTA; it’s about the young people, the residents, the artists, and the audience. I was reminded that as a nonprofit organization we only exist and people only care about what we do as it relates to the benefit and impact we’re having with people.

With the findings of the feasibility study, we struggled to get traction in raising additional support to expand into our other spaces. So we decided to approach our goal in a different way and started utilizing our other spaces in their current states. We started talking about our programs more from a perspective of opportunity for people and community needs, and ensured that we were purposefully playing to our strengths. Creating a teen and artist-staffed screen-printing production studio and retail shop is one example of this process.

Instead of suggesting that we needed to redesign buildings because “JXTA needs more space,” we talked about how could we make the most of the space we had and do more to activate the talents of local youth. This shift positioned our work in the arts as an “economic and social capital drive” in our community and investors began to see the impact we were having with young people and our broader neighborhood. After this shift our supporters became more excited to help fund our capital development projects.

Q4. How did that setback impact you and your team? Was there a repercussion from your board and funders?

Our morale took a temporary hit as our timing slowed. Four years ago when we created our strategic plan we fully intended to have a new, state of the art four-story building on the corner of Emerson and West Broadway. We haven’t accomplished that yet.

But these setbacks were not so much failures as learning experiences. They forced us to step back and examine our goal. We had to ask ourselves what we were really after. Was the goal “a state of the art four-story building” or was it what we thought that building could help us accomplish? We wanted to employ more young people. We wanted to establish north Minneapolis as a source of young creative talent for the region. We wanted to activate a vibrant street presence and spur economic development.

Once we rearticulated the goal in terms of people, the buildings just became containers for these goals. Today, we’ve accomplished all of our goals. Although we lost one funder after a mutually agreed upon parting of ways, other long-time funders started investing even more. We also have dozens of new local and national funders, customers, clients, and partners.

Q5. Can you talk more about how you have used failure, specifically public failure, as a great motivator?

I don’t really see setbacks as failure. Over my career I have learned to take the time to reflect on setbacks and discover what I can learn from them. Sometimes it requires that we find new ways to achieve a goal, and in other cases it might require us to rethink our goal.

When we launched our capital campaign there were two individuals from a local family foundation who told me they were concerned about JXTA’s capacity and our ability to accomplish our planned capital campaign.

They openly shared their doubts about me and said, “DeAnna, you are extended beyond your talents.” Later that evening I thought about that discussion and how I should have responded. I wish I had challenged them by saying: “You don’t know my talents, you don’t know me, and you don’t know how far my talents reach.” It was after that episode that I made up my mind to address their concerns and ultimately prove them wrong.

I examined how both the organization and I were perceived from the vantage point of these stakeholders. For example, I knew that we needed to shore up our communications capacity. We needed to be more consistent in how we listened and shared our current work and future plans. We needed to be more transparent with our constituents, partners, and investors. Part of what is necessary to take an organization to the next level is to bring people along on the journey so that they are walking with you. In this way the work and the support is more sustainable.

Q6. With all of JXTA’s recent accomplishments it seems like you and your organization have emerged from this experience stronger than before. Looking back, would you agree?

Absolutely! In 2004 we engaged with about 100 youth through our programs in a 2,500 square foot space. In 2010 we had 500 youth participating at JXTA as we launched our new strategic plan that included a multi-million dollar capital campaign and the creation of JXTALab, a teen-staffed design studio.

Today, even though our capital campaign has been delayed, we work with over 1,000 youth annually and employ 60 youth in year-round, part-time jobs. Our space devoted to youth creative genius and enterprise now encompasses five buildings and has grown from 2,500 square feet to 20,000 square feet. We are on our way to becoming the largest employer of youth artists in the Twin Cities. Our growing presence in the neighborhood has also helped spur more than $74 million in development by public and private investors along the 2.2 miles of West Broadway Avenue.

By every measure we have found success by moving beyond our failed capital campaign.

Q7. What advice would you give other nonprofits that are trying to create a culture of innovation within their organizations?

Honestly, we were never trying to create a culture of innovation and we still aren’t. Our goal is to do work that matters and that truly has impact with people. We wanted to do that work in a way that taps into and utilizes the best that everyone has to offer — the young people, the artists, and ourselves as leaders. By working from that perspective we have found a formula that has enabled us to be innovative. Some advice:

DeAnna and her team have done exactly what they set out to do — create a joyful, sustainable model for arts education and employment in their north Minneapolis neighborhood. They have taken several twists and turns along the way, but no one can question their talents or how far they can reach. There are many nonprofits and for-profits that would be envious of the culture of innovation they have created.

You can find more information about Juxtaposition Arts on their website at http://juxtapositionarts.org/. You can also connect with DeAnna Cummings via LinkedIn, Twitter, or through email at deanna@juxtaposition.org.

Images: Courtesy Pollen

We are constantly bombarded with the latest “innovation” stories from Silicon Valley tech startups. Almost never do we hear the stories of amazingly innovative non-profits – but trust me they do exist. As in business, sometimes innovation initiatives succeed but sometimes they miss the mark. How organizations chose to accept and learn from those failures can dramatically influence their future success. They are not just attempting to launch new initiatives, they are creating a culture of innovation.

I have tried to capture the story of one amazingly innovative non-profit – Anu Family Services, Inc. Their CEO Amelia Franck Meyer has worked hard over the last decade to build a culture that isn’t afraid to take risks as they strive to be the best in creating permanent foster care connections for our society’s most vulnerable youth. Please help me in sharing their story!

[This article was originally published on August 1st, 2014 in the online publication Pollen]

How Anu Family Services Learned Their Biggest Lesson from a Shocking Setback

Too many articles written about innovative organizations focus solely on success stories from the business world. These stories often highlight the hottest new app or the sexiest new technology. But that approach misses a whole trove of innovation that happens outside of the for-profit technology sector. Every day innovators in education, government, and nonprofit sectors seek to become world-class organizations by challenging current assumptions and trying new approaches. Sometimes these innovators will succeed, but they also have to be prepared for the possibility of failure.

Too many articles written about innovative organizations focus solely on success stories from the business world. These stories often highlight the hottest new app or the sexiest new technology. But that approach misses a whole trove of innovation that happens outside of the for-profit technology sector. Every day innovators in education, government, and nonprofit sectors seek to become world-class organizations by challenging current assumptions and trying new approaches. Sometimes these innovators will succeed, but they also have to be prepared for the possibility of failure.

A few months ago I had the opportunity to host a BushCONNECT panel discussion with the executive directors of three amazingly innovative non-profit organizations (see event video). The topic for the panel discussion centered on the role of failure in driving real change and innovation. While each story was unique, a common theme ran throughout. Each organization saw occasional failure as a necessity in driving new, innovative solutions to improve the lives of their constituents and communities. Over the remainder of the year I will bring you each of their stories.

Our first is from Amelia Franck Meyer. For 25 years Amelia has been an innovator in child welfare. For the past 13 years she has served as CEO of Anu Family Services. Amelia and her team are pioneers in creating permanence for youth living in out-of-home care. They strive to be the best at creating permanent foster care connections to loving and stable families. This is the story of how Anu Family Services created a culture of innovation.

Q1. You mentioned Anu Family Services set out to do foster care placement differently. It’s one thing for a leader to say they want to change the status quo, but how did you engage the rest of your organization to act on this idea?

We conducted an annual leadership retreat in 2006 where everyone read the following books in preparation: “Good to Great” by Jim Collins; “Built to Last” by Jim Collins; “Good to Great for Social Sectors” by Jim Collins; “The Tipping Point” by Malcolm Gladwell; and “Mavericks at Work” by William C. Taylor. We then conducted the “Good to Great Organizational Assessment,” which resulted in mutually defining our “BHAG” (Big Hairy Audacious Goal): “To be the last placement, prior to permanence, for 90 percent of the kids we served.”

We also developed a tree as an internal logo for the idea. We tied the thought of getting kids to permanence to the story of trees in the Boundary Waters. Because these roots cannot grow deeply, they are interconnected with each other for more strength. This was the basis for our idea about connections with our kids. Our kids don’t have deep roots, so they need a web of connections to keep them strong. We held a kick-off event, rallied, and involved everyone in the organization around this goal. A critical component was developing a “sense of urgency” (from author J. Kotter) by understanding what happens to the youth who leave our care if they were not able to achieve permanency. We had about 38 percent permanency when we started (four out of ten kids). We became obsessed with what happened to the other six kids. That is what drove our passion and urgency for the work.

Q2. You mentioned that in 2006 there was little data published on successful Treatment Foster Care discharge to permanency rates, and how your team wasn’t sure what a good permanency rate was. Your rate was 38 percent, but your leadership team decided to shoot for 90 percent. Can you share the story of how you came up with that aggressive goal?

Q2. You mentioned that in 2006 there was little data published on successful Treatment Foster Care discharge to permanency rates, and how your team wasn’t sure what a good permanency rate was. Your rate was 38 percent, but your leadership team decided to shoot for 90 percent. Can you share the story of how you came up with that aggressive goal?

We believe that all youth deserve and can have permanent families, but we know some kids have such significant relational trauma that they might initially need more restrictive care to keep them safe while working to heal that trauma. We estimated about 10 percent of kids couldn’t live safely with a permanent family after leaving our homes, and that they may need a safe place to stay while they worked on their grief, loss, and trauma healing. I am not aware of any data to confirm this assumption, and that was the audacious part of our BHAG. It is built on our foundational view that all children should be raised in families, preferably their own whenever safely possible. We believe that 90 percent of the time supports can be put in place to make this goal safely possible.

Q3. You knew your organization would have to approach the issue of permanency differently to achieve your goal. You mentioned the team embraced a model of “practice, try, and experiment.” How did the search begin for new ideas or ways to approach this challenge?

Q3. You knew your organization would have to approach the issue of permanency differently to achieve your goal. You mentioned the team embraced a model of “practice, try, and experiment.” How did the search begin for new ideas or ways to approach this challenge?

We knew we didn’t have these answers internally, so we began to do several things to bring new information into the organization:

Q4. You shared the story of how your team worked on a pilot with the University of Minnesota to use the family search and engagement model as a focus to help increase your permanence placement rate. Unfortunately the “solution” missed a critical issue that resulted in failure. How devastating was this failure on the child and the family? How difficult was it on your team? Did your benefactors weigh in?

In 2008 in order to get more youth to permanence, we began to utilize a model of family search and engagement to identify the individuals our youth had loved and lost through multiple out-of-home placements. We brought in the author of the model for training and felt very confident that we had found a solution to help our youth who were at risk of aging out with no one. Although we used great clinical practice and preparation, this pilot was a miserable failure. The youth acted out in violent ways after great meetings with their previously lost relatives. It was terribly disappointing and upsetting to all involved. There was great optimism and hope around this initiative, but it was an epic failure. Our funders did not weigh in, but we have shared our story widely as a way to talk about our continuous learning culture and process at Anu.

Q5. Where you able to learn from this failure? Did it help point you in a different direction?

Our big learning came from talking to our youth and others about why this process failed. Our youth were rightfully enraged with all of us! They were upset with their families because the youth felt that if their families wanted to see them, it shouldn’t have taken their families so long to find them. They were upset with us because it took us so long to find their families. They were angry they had to call eight different people “mom” in eight different foster homes over five years. What we came to learn is what we now refer to as our “golden nugget of truth”: Normal, healthy brains turn off their ability to connect after multiple, unresolved losses, especially losses of caregivers. This made it clear that we needed to find ways to heal relational trauma in order for youth to grieve their losses, heal their pain, and again be able to form healthy, stable connections.

Q6. What best practices have assisted your organization in learning from mistakes or failures?

At Anu Family Services we are dedicated to an in-depth Continuous Quality Improvement process, which has received recognition from our accrediting body, the Council on Accreditation (COA). This process, which involves representatives from all levels of the organization and utilizes some of the Collins’ “Good to Great” principles (such as “confronting the brutal facts” and “performing autopsies without blame”), helps us critically look at our practices and constantly evolve with well-informed leaps of faith.

Q7. What best practices have you found for building a team that is curious and courageous in finding new solutions?

Q7. What best practices have you found for building a team that is curious and courageous in finding new solutions?

Just as we do not “blame and shame” our youth, we do not “blame and shame” each other. We ask, “What do we need to know and learn so this doesn’t happen again?” Not, “Whose fault is it?” We are always looking for ways to improve, and we understand that mistakes are part of the process. We use data to tell a story, and we let the data speak without judgment.

We also have a collective sense of urgency that keeps us on the playground trying new things — even when it’s not going well and we just want to take our ball and go home because it’s safer. We also have a high level of trust among our team members. People are supported through their humanness, their mistakes, and their risk-taking. We are committed to doing what is right, not what is easy. We are always using the filter, “Would this be good enough for my own child?”

Q8. Are there any books or resources you would recommend for your executive director peers on building a strong, innovative organization?

Although they are older, they are tried-and-true resources for us:

Through hard work and determination, Anu Family Services has become a world-class foster care organization. The group’s ability to challenge current assumptions, try new approaches, and learn from its failures has continued to drive its success. Anu’s average placement to permanence ratio has remained higher than 55 percent for the last six years, and in 2012 the group achieved a 63 percent ratio. A benchmark ratio of top-performing treatment to foster care agencies is 45 percent, and the national average ranges from 30 to 40 percent. Anu’s focus on continuous innovation is improving the lives of its constituents and bettering our community.

Amelia Franck Meyer has chosen to make her career about helping others as a leader in the non-profit community but I have no doubt that that she would have been equally successful in leading a for-profit organization. The accomplishments of Amelia and Anu Family Services are no less innovative than the hottest new app or the sexiest new technology – they too are worthy of our attention and our praise. A thank you to Amelia and the entire Anu Family Services team!

You can find out more about Anu Family Services from their website at http://www.anufs.org. If you would like to learn more about how you can support their foster care mission or inquire about becoming a foster parent, please email info@anufs.org or afranckmeyer@anufs.org.

Images: Courtesy Pollen at www.bepollen.com

I work with companies large and small who are trying to develop a sustainable innovation practice. They don’t just want to launch an idea on a wing and a prayer. They want to find a repeatable process that can improve their chances of success. Admittedly they have tried the wing and prayer route before and they know it doesn’t work. The truth is that most of these disruptive or exponential innovation initiatives don’t succeed. They fail. The challenge that these companies face is that they are trying to build the tools and processes but they struggle to address the culture. They never address the necessity of failure.

[This post was originally published on July 23rd in LinkedIn – see The Necessity of Failure]

Last year the American Management Association (AMA) conducted a survey of 500 executives, managers, and employees asking them for their opinion on the biggest obstacle to encouraging employees to take greater responsibility (see Fear of Failure).

Last year the American Management Association (AMA) conducted a survey of 500 executives, managers, and employees asking them for their opinion on the biggest obstacle to encouraging employees to take greater responsibility (see Fear of Failure).

Far and away the largest response was the “fear of being held responsible for mistakes or failures” with 38 percent citing it as the leading cause. That is more than one third of respondents believe the fear of failure is holding employees back from taking on more responsibility or more risk in their work.

If we add in the third and fifth ranked responses the message looks even grimmer. The “Lack of incentives or deterrents in organizational processes” with 14 percent and “Reluctance to make decisions that might impact one’s career” with 9 percent we get a total of 61 percent of respondents who are too fearful of the consequences or see little incentive in taking greater responsibility. That would be almost two out of every three employees who are too afraid to take on more responsibility in their work.

Many companies are going through the right innovation motions. They are creating their innovation pipeline, experimenting with open innovation and trying to manage their front-end and back-end innovation processes but few are addressing this fear. Few are tackling the issues of risk, failure, and the consequences that follow. It is when the consequences of failure outweigh the rewards of success that innovation programs stall.

Recently I was presenting my story on how a lack of planning for failure has crippled many corporate innovation programs because it allows the risk vs reward ratio to become inverted. After the session an innovation leader at a Fortune 100 company had contacted me suggesting that “I had hit the nail on the head.” She works at one of the most innovative companies in the world and she was witnessing leaders who were not willing to take on risky initiatives because the consequences for failure outweighed the rewards. These leaders had modified their behavior to ensure their own survival.

As employees see how other innovators are being treated when their projects fail they will knowingly or unknowingly move to de-risk their own behavior. This theory of how we as humans learn from watching the actions and consequences of others was first formulated by psychologist Albert Bandura in 1977. Bandura coined the theory as Social Learning Theory.

Anyone who has spent time watching children interact will recognize the accuracy behind the theory. What many leaders fail to understand is how this behavior permeates beyond the childhood playground. This theory plays out daily in the office when we are observing the actions and the consequences of our colleagues.

So while employees are afraid to make mistakes or fail in the workplace they have ideas on how to solve this dilemma. When the same group of participants was asked what actions could be taken to encourage greater responsibility more than half of them responded “support a culture where well-reasoned risk-taking is encouraged.”

That piece is worth repeating. More than 60 percent of respondents cited “the fear and consequences of failure” as the main driver for not taking more responsibility at work and they knew that “supporting a culture where well-reasoned risk-taking is encouraged” would help address that fear. They correctly identified the issue and the solution. How is it that no one is paying attention?

If leaders want employees to fully engage in taking responsibility and driving innovation within the organization then they have to recognize the “necessity of failure” in the process. And when these failures occur it is essential that they support those employees who are willing to take on those risks to their career and compensation.

Food for thought:

A couple of additional articles on Innovation & Risk Taking:

Image Source: Youtern.com

Last year I began writing an online column for Pollen titled Facing Failure as an effort to spark a discussion on the importance of failure in driving innovation in the non-profit, education, and government sectors. Most of us would prefer to avoid failure and the pain that it can cause but to truly create something new mistakes will need to be made along the way. In politics, a “failed” initiative can quickly sabotage a political career which is why most politicians are quick to dismiss or gloss over their shortcomings. But there are some politicians are trying to reframe the discussion with candor and transparency. I am excited to share my recent interview with one such politician, former Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak.

[This interview was originally published on July 1st, 2014 in the online publication Pollen]

On Failure with Former Minneapolis Mayor, R.T. Rybak

In business, failure might cost you your bonus, that promotion, or even your job. But in the world of public politics, a failure can quickly cost you your career. Executives and politicians alike prefer to distance themselves from failures. When they do recognize a shortcoming, they cite the myriad of external factors that led to the failure as they brush it aside and head in the other direction. Not until an executive or politician has left the arena will they usually disclose their political imperfections.

In business, failure might cost you your bonus, that promotion, or even your job. But in the world of public politics, a failure can quickly cost you your career. Executives and politicians alike prefer to distance themselves from failures. When they do recognize a shortcoming, they cite the myriad of external factors that led to the failure as they brush it aside and head in the other direction. Not until an executive or politician has left the arena will they usually disclose their political imperfections.

In discussions with insiders from the Minnesota political arena, I often hear former Minneapolis mayor R.T. Rybak described as “a different breed.” Maybe it has something to do with the fact that he has been known to stage dive into concert crowds. Maybe it’s because he led the city forward in a true partnership between the community and local businesses. Or just maybe it’s because he changed the conversation with the electorate by frequently being out with constituents in the community, being more transparent with his policies, and in asking for voters to trust him in innovating government.

In a previous Pollen article (Mistakes vs. Failures), I shared my preferred distinction between a mistake and a failure in driving innovation. A mistake is an incorrect, unwise, or unfortunate decision caused by bad judgment, lack of information, or a lack of attention. A failure is simply lack of success—when something you were trying to accomplish fell short of what was required or projected. The important part is that mistakes don’t always have to end in failure and failures aren’t always caused by mistakes. The following is from a recent interview with former Minneapolis mayor R.T. Rybak on the importance of innovation in government, the risks involved, and the role of failure in the process.

MATT HUNT: In your 12 years as Minneapolis mayor, you’ve had some pretty good successes. You cite the city’s STEP-UP Summer Jobs Program, the Midtown Exchange, the Midtown Global Market, and the improved bond rating as a few of accomplishments that you’re most proud of. Of all your successes as mayor, which do you feel were the most innovative initiatives?

R.T. Rybak: There were a few that come to mind.

One initiative that took an active role in changing our community was the STEP-UP Summer Job Program. With that program, we were able to raise a lot of private money and get businesses to participate. We turned a deficit as an asset. I am proud of what we accomplished with the program and that it was a great sales pitch—we have had over 18,000 thousand participants so far and it will be over 20,000 by the end of the summer.

We very rarely get credit for infrastructure projects but when I became mayor, I had inherited a big problem. At the time, during heavy storms, raw sewage drained into the Mississippi. I was told that solving the problem would involve many millions in infrastructure. We took a comprehensive approach by disconnecting the storm sewers from the sanitation sewers and by purposefully creating a lot more water-permeable land. We added green rooftops onto the downtown Minneapolis Central Library and Target Center which I took plenty of political flack for. But the green roof on Target Center can now absorb more than 1 million gallons of water per year.

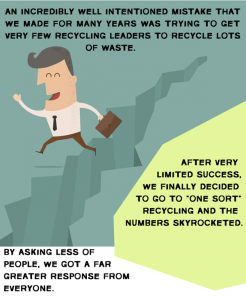

An incredibly well intentioned mistake that we made for many years was trying to get very few recycling leaders to recycle lots of waste. After very limited success, we finally decided to go to “one sort” recycling and the numbers skyrocketed. By asking less of people, we got a far greater response from everyone.

An incredibly well intentioned mistake that we made for many years was trying to get very few recycling leaders to recycle lots of waste. After very limited success, we finally decided to go to “one sort” recycling and the numbers skyrocketed. By asking less of people, we got a far greater response from everyone.

Finally, I would have to say that our Minneapolis 311 system was one of our most innovative initiatives. The system addressed the single biggest issue—residents wanted to be able to figure out who was in charge and how to get something fixed. One example of how it worked well was with public graffiti. The single biggest complaint to our office was reporting public graffiti. When the 311 team worked on the script for reporting this problem, they recognized that seven different parties were involved. So instead of taking the call and passing it on to those parties, the team eventually rewrote the process with just one person in charge. The initiative forced us to reinvent the systems behind it—we didn’t just want a phone system.

MH: There seems to be a growing consensus that we need to innovate more in the public sector if we are going to move our city, state, or country forward. But unlike the private sector where the risk of failure is understood as part of the innovation process, there seems to be little tolerance for “failure” in public sector. Do you agree? If so, how did you find balance in this paradox as mayor?

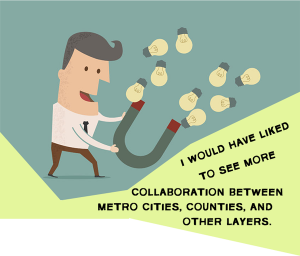

R.T.R: Yes, I agree. The reality is that it is pretty tough to run re-election if you made a mistake. I had the luxury of coming into the job of mayor in the middle of financial crisis for the city. Not changing wasn’t an option. The status quo wasn’t an option. I had a lot of support to take action. I do think that one of my biggest regrets was that we weren’t able to do more to eliminate more layers of government. There are many important roles of government but we have much more than we can afford. I would have liked to see more collaboration between metro cities, counties, and other layers.

R.T.R: Yes, I agree. The reality is that it is pretty tough to run re-election if you made a mistake. I had the luxury of coming into the job of mayor in the middle of financial crisis for the city. Not changing wasn’t an option. The status quo wasn’t an option. I had a lot of support to take action. I do think that one of my biggest regrets was that we weren’t able to do more to eliminate more layers of government. There are many important roles of government but we have much more than we can afford. I would have liked to see more collaboration between metro cities, counties, and other layers.

Another thing that I learned during my time is as mayor was that there were times when spending more in year one can save you more in year two and beyond. But that is a very difficult balance in tough times because the more you spend would have equaled less police or firefighters. We need more politicians willing to have that difficult discussion.

MH: In the private sector, there is a distinction between incremental innovation (i.e. General Mills introducing a new flavor of Cheerios) and disruptive innovation (i.e. Dayton Hudson launching a new discount concept called Target). Do you think there is a role for both kinds of innovation in the public sector? If so, where do you most see the need for disruptive innovation today?

R.T.R: Yes, we absolutely need both. I feel that the public does have more of an appetite for being a partner in solving these big problems. I saw more acceptance from voters for big sweeping changes that caused some inconvenience than for more subtle changes with less inconvenience that did not resolve the issue. My recycling story was an example of this.

R.T.R: Yes, we absolutely need both. I feel that the public does have more of an appetite for being a partner in solving these big problems. I saw more acceptance from voters for big sweeping changes that caused some inconvenience than for more subtle changes with less inconvenience that did not resolve the issue. My recycling story was an example of this.

As for where we need disruptive innovation—the single biggest thing is businesses getting ready for the coming worker shortage. From our last budget, we identified money for a work transition plan that was envisioned as an adult version of the STEP-UP Program [called] Urban Scholars. We need a solution that can get more able bodies into the workforce. I was able to help lay out the strategy but wasn’t able see it through as mayor.

MH: Last year we saw a major innovation in the way average Americans get healthcare coverage with the Affordable Care Act. The introduction of healthcare exchanges was publicly criticized for a tragically poor implementation. This issue eventually became a political lightning rod at both the state and national level. In the zero-sum game of politics, few politicians seem to have the political will to take on these large complex problems. Are we then bound to mostly incremental solutions? Is there a better way?

R.T.R: I believe that we get the politics that we deserve. If we are going to continue to see cartoons instead of looking at the facts, then we are not going to solve these problems. The truth is that 7 million more Americans have healthcare. I think that the tide is turning on this issue. There is a huge problem and politicians need to have the guts to stand up for what they know is right. It is imperfect but it is better than the status quo.

MH: Few voters remember that in 2001, Minneapolis was in serious financial trouble and its bonds had been devalued. Under your leadership, the city paid off millions in debt and worked to reform pensions. In 2013, we witnessed the first failure of a major American city when Detroit filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection. Did your team study Detroit’s failure to learn from their mistakes? Were there any lessons learned?

R.T.R: We knew early on that we needed to get our financial house in order and we made hard decisions to pay down more than $100 million dollars of debt. I have known the last two mayors of Detroit and what has happened to that city is tragic. To be honest though, I think we have learned more from other cities like ours that didn’t respond as fast to the financial crisis. We were able to come together and respond quickly. There are times to cut spending, there are times to invest, and there are times to reform—and sometimes you need all three. The good news is that we took action to ensure that what happened to Detroit won’t happen to us.

MH: In a 2013 interview, you mentioned that “a lot of people in public roles […] seem to put on a public façade.” How much of this façade do you think is to protect a candidate from his or her own shortcomings? Do you think the Minnesota electorate will stand behind a candidate who is humble enough to admit his or her failures?

MH: In a 2013 interview, you mentioned that “a lot of people in public roles […] seem to put on a public façade.” How much of this façade do you think is to protect a candidate from his or her own shortcomings? Do you think the Minnesota electorate will stand behind a candidate who is humble enough to admit his or her failures?

R.T.R: I suppose some politicians see the need to obscure the truth. I was the opposite. I give the electorate more credit. I tried to give them more information and more transparency; letting the chips fall where they may. I believe that authenticity is the best political weapon.

MH: Were there any initiatives that you undertook as mayor that you would consider a failure? Looking back are there things that you would have done differently?

R.T.R: Not everything worked like I wanted it to but the one issue I felt had the most work left to do was with our schools. That is the reason why I wanted to take the job at Generation Next.

MH: You’ve mentioned that you’re interested in potentially running for governor in 2018 and you’ve stated that you didn’t think that you were going to win your first election as mayor. If you do decide to run, what odds would you give yourself for success?

R.T.R: Honestly, I haven’t thought that much about it and probably won’t for a few years.

While we might not all agree on whether we need less government or more government, it’s easier to agree that we need effective government. Many cities and states have recognized the need to build repeatable innovation processes in order to deliver more effective government services. A few years ago, Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government published their list of “Top 25 Innovations in Government” from more than 500 applications. Most of the innovations would be considered incremental but a few of them were disruptive.

Just as in the for-profit business sector, we need our government to seek both incremental innovation projects and disruptive innovation initiatives. To do this, we need an electorate that recognizes that “innovation perfection” doesn’t exist. The truth is that mistakes will be made along the way and sometimes we will need to start over. We also need a breed of politician who have the courage to lead these pilot programs and the conviction to be transparent with the results. If we cannot build in a tolerance for potential “innovation failure” into our political process, then we are indeed bound to get the government that we deserve.

I’d like to thank former Mayor Rybak for his time, his courage, and his conviction—he truly is a different breed.

Food for thought:

Images: Courtesy Pollen at www.bepollen.com

Are we ready for a new twist on reality TV? What if we moved benign academic tussles to a new full-contact arena? We could call it the “Ph.D. Cage Match.” Not likely but I have to admit truthfully that it has been a little exciting watching this battle of words brewing between two Harvard academics. Jill Lepore (a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine and Harvard Professor of American History) and Clay Christensen (a Harvard Professor of Business Administration and the reigning godfather of the modern innovation movement) have been publicly duking it out over their disagreement on Christensen’s theory of “disruptive innovation.”

[This post was originally published on June 24th in LinkedIn – see Drama in Academia This Week.]

In a recent cover story article (The Disruption Machine) for The New Yorker, Lepore takes aim at Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation as nothing more than a theory of why companies fail and citing that it lacks little predictive value. Christensen retorts with an interview for Bloomberg’s Businessweek where he suggests that Lepore committed a “criminal act of dishonesty” and “at Harvard of all places.” The follow up stories from Slate and others suggests that the whole escapade has regressed to an Ivory League version of calling call for an elementary school fight behind the local gas station. Unfortunately the back and forth name calling doesn’t paint the whole picture.

In a recent cover story article (The Disruption Machine) for The New Yorker, Lepore takes aim at Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation as nothing more than a theory of why companies fail and citing that it lacks little predictive value. Christensen retorts with an interview for Bloomberg’s Businessweek where he suggests that Lepore committed a “criminal act of dishonesty” and “at Harvard of all places.” The follow up stories from Slate and others suggests that the whole escapade has regressed to an Ivory League version of calling call for an elementary school fight behind the local gas station. Unfortunately the back and forth name calling doesn’t paint the whole picture.

Innovation is not a cure-all for the ailing organization, like eating a healthy diet it can help the sickly but it is only one piece to a healthy lifestyle. Companies fail for many reasons and a deteriorating ability to drive disruptive innovation is just one possible reason. Pointing out an “innovative” company that has failed does not make disruptive innovation unimportant. The reason for Christensen’s success is that his message has resonated with millions of business practitioners who have observed the truth in his ideas. As startups, companies are quite familiar with risk taking, innovation, and the chances of failure but as the company grows their leaders begin to reward risk management over than risk taking. Eventually many organizations enter a wealth preservation mode where only incremental innovation survives.

Highlights from Lepore’s article in The New Yorker:

“Disruptive innovation is competitive strategy for an age seized by terror.” This is a false conclusion, an overreach, and a bit of academic hyperbole to say the least.

“Most big ideas have loud critics. Not disruption. Disruptive innovation as the explanation for how change happens has been subject to little serious criticism, partly because it’s headlong, while critical inquiry is unhurried; partly because disrupters ridicule doubters by charging them with ‘fogy-ism,’ as if to criticize a theory of change were identical to decrying change; and partly because, in its modern usage, innovation is the idea of progress jammed into a criticism-proof jack-in-the-box.” Here I think that Lepore has a point. Few companies are willing to even acknowledge their disruptive innovation failures let alone admit them in public so there is very little published in this area. I have previously post an article with data scientist Thomas Thurston on his data set of over 1000 corporate ventures from different companies in different industries. His data points to a 78% failure rate among new corporate ventures (see Connecting the Dots on Innovation).

“Disruptive innovation goes further, holding out the hope of salvation against the very damnation it describes: disrupt, and you will be saved.” This is a draw – maybe Christensen and his team are promoting a bit of hyperbole of their own but every movement needs to have a mantra and as such this one seems pretty harmless.

As for Christensen’s rebuttal in Businessweek:

“And then in a stunning reversal, she starts instead to try to discredit Clay Christensen, in a really mean way. And mean is fine, but in order to discredit me, Jill had to break all of the rules of scholarship that she accused me of breaking—in just egregious ways, truly egregious ways. In fact, every one—every one—of those points that she attempted to make [about The Innovator’s Dilemma] has been addressed in a subsequent book or article. Every one! And if she was truly a scholar as she pretends, she would have read [those]. I hope you can understand why I am mad that a woman of her stature could perform such a criminal act of dishonesty—at Harvard, of all places.” This point should go to Christensen. I am not sure it was meant to be as “mean” as he makes it out to be but Lepore did seem equally contrived in her selection of rebuttal cases. In Christensen’s defense, a book can only ever hope to be a theory at a certain snapshot in time. There are going to be positive and negative influences to the theory after publication that it can’t possibly cover. As for other authors, Christensen seems no worse in his predictive accuracy. Just re-read Jim Collins’ Built to Last for a quick confirmation.

“If [Lepore] was actually interested in the theory and cared enough about it to walk 15 minutes to talk and let me know she’s doing this, I could have listed 10 or 15 problems with the theory of disruption that truly need to be addressed and understood. I could list all kinds of problems that we still need to resolve, because a theory is developed in a process, not an event.” Here in my opinion is the root of this entire confrontation. Drama sells and The New Yorker loves to create some occasional drama. If you look at what both parties are saying they are not nearly as far off as the headlines would have you believe (see the drama perpetuate in two Slate stories from June 17 and June 23).

I would have to give the match victory to Christensen but I do agree with Lepore on several of her points. Here is a brief summary of my takeaways from the first Ph.D. Cage Match:

Image Source: wwe.com

Receive periodic email updates from Matt Hunt including his published pieces, updates on his progress, and more!