Learning from Failure… a collection of stories, insights and lessons learned.

Seven years ago my team had just shut down the first of our two concept stores that we were running for consumer electronics retailer Best Buy. My team had spent the last two years operating these concept stores in an attempt to understand more about the opportunities in “small box” retail. During that time we had learned a ton and as a leadership team we were adamant that we needed to share what we had learned with the rest of the company.

Quickly we had discovered how valuable our insights were when we helped to launch the first wave of Best Buy Mobile stores in New York City. Because of our previous failures we knew what we would do different the next time. For example, we knew how important our decision in IT point of sale (POS) systems would be to the future success of these next stores.

In the early 2000’s Best Buy was growing rapidly and they were willing to try many new business ventures. As with most corporate ventures a majority of them would end up failing (see the post Connecting the Dots). But at the time the company lacked the discipline to ensure that these failures were documented and shared throughout the organization.

Without that process few employees inside the company would have the chance to learn from them. The fact that failures weren’t shared is completely understandable though. At Best Buy, as with almost every other company, failures were seen as a negative mark on a leader’s reputation. Many leaders would have preferred that their failures just went away.

Fortunately my team and I had an example of what good could look like in documenting an internal failure. A few years earlier JJ Schaidler, a vice president in our Entertainment group, had written an internal whitepaper on Best Buy’s failed entertainment media label – Redline Entertainment. By demonstrating personal courage in sharing her team’s journey JJ had paved the way for me and my team to share the lessons from our failures.

This article was originally published on November 15th in Innovation Excellence:

Failure Forums: Learning from Best Buy Media Label ‘Redline Entertainment’

In the early 2000s Best Buy launched their first entertainment media label Redline Entertainment. The goal was to help grow the organization vertically into the entertainment industry.

In the early 2000s Best Buy launched their first entertainment media label Redline Entertainment. The goal was to help grow the organization vertically into the entertainment industry.

As an entertainment label Best Buy would sign artists to create new material, produce the content, and provided distribution of the final products into retail outlets – Best Buy stores and others. This was a new area for Best Buy but it was tangent to their core business of selling electronics, appliances, and media. Coming off of a successful national expansion Best Buy had strong momentum and it was hungry for opportunities to continue to grow their business.

Jennifer “JJ” Schaidler had unknowingly altered her career when she took the lead role in building out Redline Entertainment. As with many innovation projects the team had a good plan in place but without all of the pieces together it would be almost impossible to test individual hypothesis. Redline’s success didn’t hinge on just one element but on a series of organizational errors that JJ documented for the company in what came to be known as the Redline Whitepaper.

What makes JJ’s story unique is that she not only was willing to own her mistakes but she was willing to document them and share them with others inside the organization. Many executives would cower from this idea as career suicide but not JJ. During my tenure at Best Buy, JJ’s Redline Whitepaper had provided an example of what good innovation work should look like: build your hypothesis, test your hypothesis, and share the results of your tests – good or bad. This is JJ’s story.

1. So Redline Entertainment was going to be Best Buy’s entertainment media label. How did that idea come about?

Our Senior Vice President of Entertainment, Gary Arnold, had the idea of growing our business by creating our own label and developing our own content. This was right around the time that Best Buy had purchased Musicland (including Sam Goody) and Future Shop in Canada. The idea had come from two concepts: 1) that the combined entities offered a huge distribution channel and 2) the artists were becoming increasingly frustrated with their labels and their binding contracts. The plan was that Best Buy could go straight to the artists and offer distribution but allow them to own their masters.

At that same time, Best Buy was defining the ecosystems that they wanted to grow and expand into diverse businesses –even non-retail businesses. Entertainment was one of those ecosystems. Starting a label seemed like an adjacent idea where we could bring the leverage of the enterprise with all of the storefront assets. We had been developing direct relationships with the artists and had connections within the manager community.

A critical piece to the puzzle was that Redline also had a distribution relationship with RED distribution (no affiliation). RED was the independent arm of SONY distribution and they were in theory able to get Redline products into Target, Wal-Mart and all the rest of the music retailers. That foot print would allow us to offer the same distribution as a major label. The advantage would come from additional marketing and advertising from the Best Buy entities.

Ultimately the competitive nature of the other retailers was the undoing of Redline. They knew that the products from Redline came from Best Buy and they didn’t want to support a competitor.

2. When you committed to the project did you consider what would happen if you failed? What kind of odds were you giving yourself for success?

I actually thought there was a likelihood of failure but it didn’t concern me. My perspective was that the company was growing so fast that it would find a place for me. In retrospect, I should have been more concerned. Only after I had taken this new role was it clear to me that going back to my old role as Vice President of Advertising wasn’t an option.

3. Where there ever expectations set by the company for what would happen if things didn’t work out?

No. Truthfully we had never done these types of innovation projects before so it wasn’t discussed.

4. How long did the project last? What was the ratio of the time spent planning vs. executing?

Around two years. The planning phase was really getting the business plan approved and that took 3-6 months. Execution or “signing” of artists and projects were started before the plan had full approval.

5. Was there ever a clear indication that they project wasn’t going to succeed?

Yes, there were several factors that popped up where we knew that we had problems: 1) our inability to get significant radio air play for our artists – radio was still a driving force behind sales, 2) the resistance/refusal from Target / Wal-Mart to buy Redline products, and 3) the lack of incoming revenue while signing on new projects. If we were starting our own external company we would expect there to be a lag while building the portfolio of business but within a corporation there quickly needed to be something that was showing a positive return.

6. What was the most difficult task in shutting the business down?

For me the most difficult task was letting go of our people. The truth was that they didn’t do anything wrong. It wasn’t their fault. Many people did find other roles at Best Buy so we were pretty successful at transitioning but for those that didn’t make the transition it was painful.

7. After you had shutdown Redline you did something that had never been done before at Best Buy, you wrote a formal whitepaper on what had been learned through the project. Can you explain why and how that happened?

In a budget presentation with the President, he commented that “I’d be happy to lose $7m dollars on Redline if we really learned something from it.” In addition, he was always referencing the Clay Christensen book – Innovator’s Dilemma. I read the book and believed that Best Buy was exactly in that classic problem. So I wrote the white paper as a way of illustrating to the company that we would need to change how we do innovation if we wanted to succeed. At that same time Best Buy had hired the consulting firm Strategos to help build out an innovation process. I participated in that work and witnessed many of the same problems repeating themselves. When Best Buy hired Kal Patel, he read the white paper and encouraged others who were trying to innovate read it. It ended up taking on a life of its own. That was good because in one sense – it was a $7m white paper. Too bad I didn’t get any royalty payments on it!

8. Have you used the lessons from Redline’s failure in your work since then?

I still get emails from time-to-time from people asking me to send it to them. The frequent comments are that not much has changed since it was written in 2002. The bottom-line is that innovation inside of large organizations is very difficult. It takes people that are willing to take risks and willing to fail. When a company is growing and has the funds to support innovation it makes it less risky. Public corporations that need to report quarterly profits are also extremely tough. When the numbers aren’t looking good, new ideas that just haven’t had enough time to turn a profit are the easiest to cut. In our estimation Redline needed five years. It only had two. There was no appetite to wait that long.

Following her role with Redline, JJ went on to lead many other strategic initiatives at Best Buy, including the initial launch of the Best Buy & Carphone Warehouse joint venture – Best Buy Mobile. She continues to take risks in order to drive innovation in her work and in her career by continually defining new opportunities. JJ is currently General Manager for Brightstar – the world’s largest specialized wireless distributor and mobile service company.

Most leaders want their organizations to be innovative but just saying it isn’t enough. If they want their people to take risks and innovate they have to create a culture that can support and endure the ups and the downs of driving innovation. Driving sustained innovation requires the right people, processes, & tools.

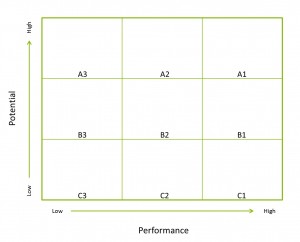

In a recent discussion with human resource professionals we examined how one of the most used tools to evaluate “employee performance” was fundamentally flawed. By not taking into account the difficulty of the work the “Nine Box” performance management tool was misrepresenting top performers and killing innovation.

This article originally ran in Business 2 Community:

As the end of the year approaches many organizations are going to be plodding through their annual employee rating process. A common tool for coordinating this work is the Nine Box Talent Management grid. With this tool every employee is placed into one of nine boxes along two axes (usually Potential and Performance) for the purpose of rating and ranking them. The results of this ranking can be used to determine bonus payouts, promotion eligibility, or succession planning. Having used this tool for over a decade, I can say that it is great in its simplicity but it is fundamentally flawed. It doesn’t take into account the difficulty of the work and it over rewards superior performance of low risk activities.

As the end of the year approaches many organizations are going to be plodding through their annual employee rating process. A common tool for coordinating this work is the Nine Box Talent Management grid. With this tool every employee is placed into one of nine boxes along two axes (usually Potential and Performance) for the purpose of rating and ranking them. The results of this ranking can be used to determine bonus payouts, promotion eligibility, or succession planning. Having used this tool for over a decade, I can say that it is great in its simplicity but it is fundamentally flawed. It doesn’t take into account the difficulty of the work and it over rewards superior performance of low risk activities.

A quick analogy from the sport of competitive diving can help make this point more clear. Before the diver takes to the platform each dive has already be rated with a degree of difficulty. The degree of difficulty rating determines the maximum and minimum point range that can be achieved for each dive. If two divers perform their different dives equally well but one has a higher degree of difficulty then that diver will receive more points. If you choose to go for the dive with the highest degree of difficulty and perform it well and you can take home the gold medal. But if you make a mistake on that difficult dive you can still achieve a higher score compared to those with perfect dives that are less difficult.

What the Nine Box lacks is the ability to evaluate the difficulty of the work when it compares employees across roles and business units.

The Director of Human Resources for a company with 9000 employees recently shared her organization’s challenge with the Nine Box rating system. What they found was that “top performers” who were in the A1 box sometimes struggled when they took on especially challenging projects. The organization’s leaders had noticed that there was a strong correlation between when the project struggled and when the employee struggled. Subsequently these star employees would get a dramatically lower rating on their next Nine Box review.

But had this individual really changed? Had they intentionally let their work “performance” drop off? A more likely scenario was that the rating system was misrepresenting the difficulty involved in their latest project? Unfortunately their struggle with the project was also diminishing their perceived potential.

But had this individual really changed? Had they intentionally let their work “performance” drop off? A more likely scenario was that the rating system was misrepresenting the difficulty involved in their latest project? Unfortunately their struggle with the project was also diminishing their perceived potential.

In my time at consumer electronics retailer Best Buy I watched us mistakenly use this tool across job levels within the organization to the detriment of our employees. We were comparing individuals responsible for running a stable “core” business with others that were responsible for launching a new product category. The degree of difficult was vastly different in these roles but it was not factored into the equation. The downgraded ranking would leave the risk taker to wonder if their innovation work was worth the price. To protect their own self-interest many employees chose instead to outperform in roles that were more certain and stable.

If your organization wants to drive growth through new products and services you need to examine how your internal systems and tools are manipulating the risk vs. reward equation for employees.

Building new products or services will involve many unknowns and inherently will have a higher degree of difficulty. If you want your best employees to continue to take on these risky initiatives you need to ensure that your performance management tools are able to evaluate them accurately based on the degree of difficulty.

Photo Courtesy: Quinn Rooney & About.com

When working with organizations I frequently talk about the need to build a “Propensity for Action” in order to support driving growth and innovation. With many for profit, and nonprofit, organizations it is far too easy to cower behind the “Tyranny of No” rather than building a culture of action around the tools of hypothesis, test, and verify. A frequently response from leaders is that new ideas are too costly or too risky to take on but if the alternative is waiting for the perfect answer it can be equally damaging to an organization. The challenge is that the odds are stacked against new ideas and most of them will not work out at planned – they will fail. The irony is that unless you are willing to take action and risk possible failure you will remain stuck with the status quo.

A friend and former colleague, Kari Kehr, wasn’t willing to stick with the status quo when she started her nonprofit foundation Fuel Your Fight. Kari had just helped a good friend through end stage cancer and saw firsthand the difficulties that singles faced in fighting their disease and in managing all the other aspects of their lives. Specifically she saw the struggle in keeping up with the mounting medical bills. Having raised money for numerous cancer groups before Kari knew what was involved in fundraising and went into action to create a foundation that could help singles in their fight with cancer.

After raising tens of thousands of dollars in their first full year of operation, Kari and her volunteer board of directors recognized that the effort required to sustain the organization was too great. She readily admits that she underestimated the difference in effort required to run a foundation versus fundraising for an organization. While they have shut down the fundraising arm of the organization they continue to help those fighting cancer find resources and information.

Kari and her board took action to help solve a problem,

as a result they have changed lives: their grantees, their donors, and their own.

This is the story of Kari and the Fuel Your Fight foundation that originally ran in the November 1st issue of the online publication Pollen.

Facing Failure: Shutting Down the Nonprofit You Founded

After a decade and raising more than $100,000 for national organizations like Susan G. Komen and LIVESTRONG, Minnesota native Kari Kehr wanted to specifically help cancer patients in her home state.

After a decade and raising more than $100,000 for national organizations like Susan G. Komen and LIVESTRONG, Minnesota native Kari Kehr wanted to specifically help cancer patients in her home state.

In 2012, Kari started a nonprofit to help single people who were fighting cancer by assisting them with the payment of distracting medical bills. A few years earlier, Kari had lost a close friend in her battle with cancer and saw firsthand just how distracting those bills could be. She recognized how singles lack the financial and emotional support of a spouse or significant other during this very difficult time.

Through the hard work of volunteers and the generosity of donors the foundation had quickly raised tens of thousands of dollars to help pay the medical bills of Minnesota singles struggling in their fight with cancer. Things were taking off but Kari quickly understood the amount of effort that would be required to keep the organization going. This year she determined that the organization was not sustainable. In the first year Kari had shouldered a bulk of the enormous effort in addition to her day job. For her it was an exceptionally difficult decision to shut down the Fuel Your Fight foundation but she knew that she could better use her time and skills to help other organizations. This is Kari’s story.

Q1: What had prompted you to create your own nonprofit?

A. Four years ago I helped my friend through end stage cancer. As I watched her battle the disease I also watch as she had the stress of a looming medical bill she needed to pay. Instead of focusing on her health, she was worried about how to pay this bill. Her friends and I created a benefit for her and raised the money to pay her bills but it brought to light the need to help others in same situation. Single cancer patients didn’t have a spouse’s salary or benefits to count on. I wanted to create a foundation that helped people like Cathy to pay their bills and alleviate that stress during their fight.

Q2: What were some of the biggest challenges in leading your nonprofit with a team of volunteers?

A. The first thing I needed to learn was how to lead friends. Our board was composed of people in my life that believed in the mission and wanted to help. That was an adjustment for me to lead as a leader and not to just ask as a friend. We all respect one another and brought different talents to the table. Leading a volunteer board was never an issue, however finding volunteers that could commit to leading work for our organization was a big challenge and one that I didn’t anticipate.

Q3: What was your fondest memory of the work?

Some of my best memories were speaking with people about their cancer experiences and offering them support both emotionally and through the resources page on our website. People want to know someone is there to support them; it was a great feeling to have them know our foundation could be that in their time of need.

Q4: What was the turning point for you when you decided that the work wasn’t sustainable?

Getting word out that we were here to help others was difficult. We didn’t plan for marketing. We were naïve to think we would form and people would hear about us through word of mouth and we would be successful. What we learned was, with all the nonprofits out there, we seemed to be lacking the awareness to grow our support system and identify recipients for our grants.

Q5: How hard was the decision to shut down your nonprofit?

I knew for about five months before we made the actual decision to shut down. We tried every which way to grow our organization. I met with other nonprofits to learn their best practices and heard over and over we would need a full time person working to grow it in order to be successful. Our board of directors was made up of four women with big full-time jobs. Our passion was there, but the time commitment was not possible.

When we finally made the actual announcement to close down it was very emotional for me. This work had been a personal mission to make a difference in the name of my friend Cathy. I had to work through the emotions of feeling like a failure by closing down the nonprofit. I knew that ultimately it was the right decision but it was still extremely sad.

Q6: So where do you and Fuel Your Fight go from here?

I have always supported the LIVESTRONG foundation and their cancer programs. I plan to continue that work and also get involved with the Angel Foundation here in Minneapolis. It is important to me to maintain my fight in the Twin Cities area. The Angel Foundation is local and helps Minnesotan’s with household expenses while fighting cancer. They are very similar to Fuel Your Fight and we believe that they were a perfect nonprofit to donate our funds to.

Even though Fuel Your Fight is dissolved our webpage is still live. A very important piece of our site was a one-stop shop for resources for cancer patients and their loved ones, and I plan to maintain the site for that and my blog about cancer on a personal level. It is a great feeling to be able to refer people to that site and have them find help… it is where my passion still lies.

Q7. Looking back is there anything that you would have done differently?

Looking back I should have done a “competitive analysis” of what it takes to run a nonprofit. The raising of funds had come easy to me, so I had thought the rest would be also. It wasn’t. We should have met with other nonprofits to learn what it takes to be successful, and then moved forward.

Q8. Where there any resources that you found helpful in setting up your nonprofit organization?

When setting up our 501c3, we utilized a guidebook that the State of Minnesota had on their website to determine how to legally set up a nonprofit. The state offers quite a bit of information on their website. Here are links to a few online resources to help if you’re thinking about starting a nonprofit.

Image courtesy: BePollen.com

I often talk with business leaders about the need to build in a tolerance for risk taking and potential failure if they want to drive growth and innovate. Frequently I get asked if there are specific areas where we should not tolerate failure? My standard response is that Accounting would be one of those areas where organizations should be very cautious with “innovation” and the potential for failure. This story from today’s headlines in another such area.

Today Ford Motor Company announced a recall on their F-Series ambulances because of a problem that can cause the vehicle to stop unexpectedly. According to Ford, the vehicles have a faulty gas temperature sensor that can cause the engine to shutdown and not be restarted for an hour (Pioneer Press: Ford recalls ambulances because engines can stop).

Ford recalling ambulances because of engine problems that could halt vehicles for at least an hour: http://t.co/FnworpoQJb

— Pioneer Press (@PioneerPress) November 1, 2013

Recognizing the role of failure in driving growth and innovation is an imperative for organizations but building a tolerance for failure doesn’t mean it should be accepted everywhere.

I am curious to hear your thoughts on where else should failure not be accepted. What areas within your organization should strive to be failure free?

Innovation projects fail for many reasons but often times the reasons point back to a disconnect with the customer or within the company. Sometimes the customers weren’t sufficiently ready to buy or use the new product or service. Maybe they didn’t yet understand the benefits, they weren’t comfortable enough with the novelty, or maybe they lacked the infrastructure to take full advantage of the new product or service? There are an equal number of examples where companies were unable to operationalize the new product or service and had to abandon it. But sometimes new innovations fail because a company can’t get out of its own way. The story of Best Buy and their development of the innovative gift registry platform GIFTAG is just one of those stories.

In 2008, Best Buy launched a universal gift registry call GIFTAG. Knowing that most customers would want holiday or birthday gifts from more locations than just Best Buy the tool was designed to allow users to capture products from any site on the Internet and add it to their personal gift registry.

An internal Best Buy development team was able to use cloud based tools to create a new product both quickly and cheaply. The challenge was that executives were skeptical that anything done so “quick and cheap” could also be a quality product. During my years in information technology I would often see leaders stick with the “traditional” vendors or methods because they were too afraid of what would happen if they failed. They feared that they might jeopardize their career if their initiative failed.

The following is a reprint of the story of GIFTAG from the individuals who were involved in building it.

The Failure of GIFTAG (for the cost of discovery)

In the Spring/Summer of 2008, the iPhone was gaining steam but the smartphone revolution was in its infancy. Facebook was still on campus. The social web was still emerging. Internet Explorer was the most popular browser among all internet users worldwide – Safari and Firefox were dwarfed by comparison. Google Chrome did not exist yet.

In the Spring/Summer of 2008, the iPhone was gaining steam but the smartphone revolution was in its infancy. Facebook was still on campus. The social web was still emerging. Internet Explorer was the most popular browser among all internet users worldwide – Safari and Firefox were dwarfed by comparison. Google Chrome did not exist yet.

During that time, Best Buy was in the midst of a great run. The company was profitable, flush with cash, and holding a dominant position in global retail. The halls were constantly filled with happy excited faces and the future looked bright.

Our group inside Best Buy was known as The Bistro. We were comprised mostly of contractors – designers, developers, and product people. Our work was a mix of experimental and enterprise-grade applications and data services. We were called upon by various entities within Best Buy to solve problems usually associated with marketing, user experience and digital product development.

The Bistro was often working on a few experimental ideas in parallel with funded project work.

One such experiment was in response to a challenge from Best Buy founder and former Board Chairman, Dick Schulze. He was on a mission. He was on a mission to launch a Best Buy gift registry. Best Buy had tried to start a registry in years past and failed. After holiday season 2007, Dick was committed to launching a gift registry before holiday season 2008.

In response to Mr. Schulze’s challenge, The Bistro conceived a modern registry that would contradict conventional wisdom. We would consider how the user wanted to shop as the first order of business.

At that time, the Target gift registry experience was an example of what good looked like. Customers could scan product in stores (with a scanner gun), add items to a list, and invite friends to buy items from the list by telling them of the registry. The list could be viewed and printed from kiosks in the store. It was a solid brick and mortar solution.

We imagined a registry that would work to help a user with the pre-shopping that they were doing online before making their store visit. We recognized that Best Buy shoppers were event based shoppers (i.e. holidays, birthdays, home remodeling). We knew those shoppers were also shopping several other retailers for the same event. For example, you will probably not purchase all your holiday gifts from Best Buy.

GIFTAG, a universal gift registry, was born in the Spring of 2008 and launched in the Fall (at DemoFall 2008). GIFTAG was comprised of several components. To the user, it was a web interface with accompanying browser plugins and bookmarklets for IE and Firefox. The backend application was converted to run on Google App Engine.

Our choice to use Google Cloud products for GIFTAG introduced a new advantage to The Bistro. We were now able to conceive, create and deploy a scalable working application prototype in the time it took other teams to order, receive and configure a server. Our speed to working code created a lot of disbelief in an organization that was accustomed to spending and $50k-$200k to have their on-site consultant run a “discovery” project. That discovery project would yield a seven figure development proposal and the need for hundreds of thousands of dollars in hosting and server administration.

We were building enterprise-grade, scalable applications for the cost of discovery.

In some ways, GIFTAG was a success. GIFTAG was never marketed or integrated with the BestBuy.com user experience. It ran without an error or any significant downtime until 2012 when The Bistro turned it off. At the time, GIFTAG was fielding about 50,000 organic visits per month.

A confluence of factors contributed to GIFTAG’s glorious failure. It wasn’t a seven figure project so how could it possibly be good enough, powerful enough, durable enough, and secure enough? Aren’t customers going to shop at other retailers with it since it’s universal? How is it going to work if it’s not integrated at POS?

These questions and others were enough for the organization to set GIFTAG aside and pursue a more traditional project approach.

Image courtesy: djangosites.org

SimonDelivers had launched as a online grocery delivery business in 1999 at the height of the Dot.com boom. By 2001 many of their competitors had imploded in the Dot.com bust. Miraculously SimonDelivers had managed to be one of the few that weathered the storm only to be later caught up in the real estate bust of 2008. Often times we can learn more from failures of others than from their successes. This story is a glimpse into the lessons learned from the failure of SimonDelivers.

This article is my second in a new series for Innovation Excellence titled Failure Forums:

Failure Forums: Lessons From SimonDelivers – a failure to change customer habits

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a new monthly series titled Failure Forums. The series is focused on bringing the role of innovation failure to the forefront and will intentionally bypass the innovation success stories to focus on the lessons learned from failures. It is never easy to disclose our professional failures but these brave innovation practitioners are doing exactly that so that others can learn from their experiences. We hope you will enjoy this new angle on driving innovation.

In the late 1990’s it seemed as if everyone was leaving their stable jobs to join hot tech startups. Like so many others, Steve Lauder had the entrepreneurial spirit and saw amazing opportunities ahead of him. In 1998, he left Minnesota based grocery retailer SUPERVALU to join a couple of high risk startups. First he joined Drugstore.com and then in 2000 he jumped to online grocery retailer SimonDelivers as Vice President of Product and Procurement. SimonDelivers had just launched but it would soon feel the repercussions of the Dot.com bust in 2001. Miraculously it had managed to be one of the few that weathered the storm. The West Coast online grocery service Webvan, the pioneer in this space, wasn’t so lucky and it ended up going bankrupt in 2001.

SimonDelivers had been ahead of its time in logistics, supply chain, customer service, B2B sales and CRM but it couldn’t handle the weight of another crisis – the economic recession of 2008 had tightened credit markets and many investors were hunkering down for the approaching storm. In the summer of 2008 SimonDelivers had ceased operations. Within a few months the assets were purchased and the business was re-launched by another local grocer as CoburnsDelivers. Ask Steve today about his experience at SimonDelivers and he will tell you there isn’t a thing that he would have changed about his journey – he has learned so much. This is Steve’s story.

1. You left Supervalu to join a couple of high risk startups in the early Dot.com boom days. How did you see the decision to join Drugstore.com and then SimonDelivers at the time?

The decision was more about my core personality traits than about companies. SUPERVALU could provide a great career, but it would be a slow career … managing “between the lines” and mitigating risks. Innovation experimentation and interest in building things were not going to be part of that path, which is what pointed me toward start-ups. So while co-workers at SUPERVALU questioned why I would move my family across the country and take such risks, I only saw opportunity.

2. When you committed to join SimonDelivers did you consider what would happen if you failed?

No, I really believed in the concept and wanted to work on it very badly. I thrived on the pure excitement of being part of something new and challenging. I always appreciated that I was learning at a faster pace than most others in my career, and I would walk away smarter – no doubt! I guess that’s the great part of taking risks: you learn a lot, regardless of outcome.

3. What kind of odds were you giving the company for success?

Interestingly, those types of thoughts/calculations never entered my mind. I am not saying we never had rough days, but we just kept moving forward. Over time, some people in the company reached a point where the risk of staying was too great for them, so they left. But most of the time we were really just focused on hitting our goals.

4. SimonDelivers had survived the Dot.com Bust but not the Real Estate Bust. What was different the second time?

I think investor fatigue had more to do with the ultimate sale of SimonDlivers.com than market conditions. Many of the funds had been invested for a long time — probably beyond their normal guidelines. The core business continued improving, but maybe they were just past the point of wanting return on investment.

5. You have mentioned before that SimonDelivers had survived for eight years but had been asking the wrong question all along. Can you explain?

SimonDelivers is a great business case study. The company was ahead of its time in logistics, supply chain, customer service, B2B sales and CRM. But a series of very talented CMOs could never get a handle on what the company called the “leaky bucket.”

The foundation of the business, and the investment in warehouse, trucks etc., was based on achieving a certain penetration percentage of the market. We could attract trial customers, but never really grew our loyal base. Numerous efforts were undertaken to understand what was wrong. We looked at service failures, lack of assortment, pricing … all of the normal triggers.

When the task of figuring this out made it to me, I teamed with two great partners – a database geek and a classic direct marketer. We came up with the idea of layering demographic data with behavioral data. I have a vivid memory of staring at the data in a conference room and sitting back and saying, “Wow! The good news is that we have penetrated our market to 95%. And the bad news? We have penetrated our market to 95%.”

What that meant was consumers who fit both the demographic and attitudinal characteristics were only 50% of the assumed base in the original plan. Customers loved us, but the majority did not shop with us regularly because they never changed their habit of grocery shopping.

6. Back in the day there were always rumors that Amazon might acquire SimonDelivers. Was there ever any truth to the rumors?

Not really. SimonDelivers investors pursued multiple options, partnerships, direct sale. Amazon, Wal-Mart and others were happy to entertain conversations, but it is my opinion that they simply were gathering intelligence. It seemed that they had no real intent to become buyers or investors.

7. You mentioned that you had worked with Amazon previously. What was it like working with them?

Drugstore.com had a close relationship with Amazon. Jeff Bezos was on the board for a number of years. It was clear to me at the time that our model of shipping high-value, low-weight, low-cube items intrigued Amazon. Having the partnership/investment from Amazon was like having a big brother. Sometimes they looked out for you and helped you grow, and sometimes they beat you up.

8. In your days at SimonDelivers was there ever a clear indication that the company wasn’t going to succeed?

Yes. I had a moment of clarity on that day in the conference room. After years of studying consumer data and appreciating the difficulty of changing consumer behavior it became clear to me. If we couldn’t reorganize our cost structure and match our operation to the true market potential, we would continue to burn cash. Soon afterward, I left the company. For about another year, there were valiant efforts to keep attracting a new base, but eventually the company was purchased by a group who could address the underlying cost structure. The new ownership continues to deliver groceries today, in the Twin Cities market.

9. How often do you find yourself drawing on the lessons learned from the failure of SimonDelivers in your current work?

There are three lessons I keep with me every day:

After leaving SimonDelivers Steve has retained that curious “entrepreneurial spirit.” He is Senior Vice President of Innovation at financial services firm CPP North America. Pouring your blood, sweat, and tears into a startup that fails can take an emotional toll but it usually involves learning a lot along the way. Steve survived the failure of SimonDelivers but has emerged as a smarter innovator on the other side.

Failure knows no distinction to whether our institution is in business, government, education, or the nonprofit sector. Facing Failure is a new monthly series that I have launched today with the civic-minded publication Pollen. The goal for this column is to bring the topic of failure to the forefront of our civic conversations in an attempt to remove the negative stigma. I intend to do this by sharing stories and the lessons learned from business, nonprofit, education, and government sector failures. The best hope for this column would be that we are able to learn from each other and strengthen our Pollen community. If you have a story that you would like to share please reach out and connect via my contact information below.

From the October 1st Pollen publication:

Pure and simple, a failure is when something that we were trying to accomplish fell short of what was required or projected.

There is no inherent blame or shame in the word itself although it is often inferred. The reality is that we all “fail” to reach expectations on a daily basis in our personal and professional lives.

Failure knows no distinction to whether our institution is in business, government, education, or the nonprofit sector.

Because of the negatives consequences of failure, many of us have fallen into the trap of avoiding our failures and thus frequently not learning from them. But this doesn’t have to be the case. Instead if we choose to understand and openly address our issues with failure, we can ensure that we are learning from them. What does it look like when we use this knowledge to strengthen our institutions rather than discard these lessons due to embarrassment and shame?

Mistake vs. Failure

A mistake is an incorrect, unwise, or unfortunate act or decision. A mistake can be caused by bad judgment, a lack of information, or a lack of attention to detail. While a mistake can lead to failure they don’t always have to end in failure. We make numerous mistakes every day without serious consequence. We would prefer to avoid making mistakes but without perfect attention and perfect prediction they are inevitable. Conversely, a failure doesn’t always have to stem from a mistake.

Over the last two decades of my career I have spent most of my time trying to build new business platforms, first as a systems programmer and later driving innovation and new business development. Oftentimes things wouldn’t go exactly as we had planned. We would recognize this and would make adjustments along the way. As a programmer, this was a completely natural state of the world. You would write code, you would test the code, and then you would fix the bugs in the code. As I moved out of the programming world I noticed that everyone seemed less and less tolerant of making errors.

At times I have witnessed executives intentionally trying to cover up their failures by sweeping them under the rug and heading in the opposite direction. While disappointing, I came to believe that this too was a natural state of the world. Most executives don’t get promoted to the C-suite based on their long list of failures. Many have gotten promoted in spite of their failures but never because of them. Failure in business often times meant missing that promotion, losing that bonus or even getting fired.

The problem with continually avoiding our failures is that we never actually learn from them. We are too busy shoving them under the rug to step back and dissect what had happened. As such, we will frequently repeat the same errors. During my last stint in the corporate world I tried to address this issue. For two years I ran a series of “Failure Forums” at Best Buy where company leaders would share their insights from their failed initiatives. They would get up in front of the company and share what they had accomplished, what they had learned, and what they would have done differently. We would follow up each presentation with a question and answer session with the audience.

Originally I thought the problem of avoiding failures was unique to my organization. As I shared this work with others outside of my company I learned that it was an epidemic in many large organizations.

As I have continued my research on failure for my writing and consulting I was surprised to see how prevalent the issue is beyond the competitive business world. The fear, stigma, and consequences of failure are just as real but for slightly different reasons. In many of these organizations the job security and compensation issue is still a concern but more important is the consideration that failure can risk the survival of the organization. With many nonprofit organizations a large portion of their funding is from foundation grants and large donors. The rationale behind the fear is that if those groups suspect that an organization is not competent or is using their money unwisely (i.e. failing too much) they could pull their funding. For nonprofits, reputation is everything when seeking funding.

Facing Failure in Sub-Saharan Africa

A great example of this challenge comes from the work of Ashley Good (@admitfailure), formerly with Engineers without Borders Canada (EWBC). She has been pressing the issue of failure in the nonprofit space for years. While at EWBC, Ashley started an Annual Failure Report in an attempt to shine a light on failures from development organizations. Her goal was for organizations to learn from the failures of others so that they would not be repeated. One of the failure stories was from a group involved in digging wells in Sub-Saharan Africa. The organization had gone back years later to check on the wells and found that many of them were no longer working. The wells had needed to be maintained but the group had failed to train anyone to fix them or to alert someone who could help when the well had broken.

Failure in this arena is much bigger than missing that promotion, losing that bonus, or even getting fired – failure in third world development projects could cost lives. If these development organizations are not sharing their failures with the other organizations that are attempting similar initiatives then they are only propagating their failures.

This is just one example on the importance of learning from our failures but there is so much more that we can be doing.

If you have a story or insight that you would like to share please reach out to me via email at matt@matthunt.co or on Twitter @huntm. I will do my best to make sure that these stories are shared so that we can all learn together.

Receive periodic email updates from Matt Hunt including his published pieces, updates on his progress, and more!