Learning from Failure… a collection of stories, insights and lessons learned.

I see patterns. Fear not, this isn’t the introduction to a new M. Night Shyamalan movie but I do enjoy opportunities where I can connect the dots. Maybe it is the linear, logical, left –brain, former programmer in me but I relish when I find patterns that emerge across different disciplines, groups, organizations, etc. Five years ago I was part of a public policy group that mixed professionals from different worlds – for-profit, nonprofit, government, education, etc. The goal of the program was to advance public policy awareness and build public policy leadership. What I quickly recognized was that many of the same issues that were challenging me in the “for-profit innovation arena” were also plaguing these other groups. The challenges of funding, personal & organizational risk, managing expectations, and the fear or failure were consistent. There were some nuances but there was far more similarity that difference.

This article is my first in a three part series specifically focused on Driving Nonprofit Innovation. I’ve broken it into three pieces to make it easier to digest: 1) Managing the Process from Idea to Launch, 2) The Challenges of Funding Nonprofit Innovation, and 3) Building the Culture & Skills for Sustained Innovation.

This article is my first in a three part series specifically focused on Driving Nonprofit Innovation. I’ve broken it into three pieces to make it easier to digest: 1) Managing the Process from Idea to Launch, 2) The Challenges of Funding Nonprofit Innovation, and 3) Building the Culture & Skills for Sustained Innovation.

During discussions with nonprofit leaders the first concern with innovation programs is always how to manage the process: too many ideas, too few people, too little time, and too much risk. This is what I have learned.

Starting the innovation journey

Most nonprofit leaders have new ideas flooding in all of the time. How they might improve their organization, expand their services, and expand their reach. These ideas come from every group of stakeholders: board members, funders, employees and clients. The challenge for most nonprofit organizations is not a shortage of ideas but a shortage of resources. This is the identical problem that for-profit startups have. Where will the money come and who will lead and support each of these great ideas?

Sorting through of the opportunities is usually the first challenge. Which will provide the best material benefit to the organization but not consume too many resources? Being able to answering this question is necessary for defining an innovation strategy for your organization; a process that will take effort, patience, and focus.

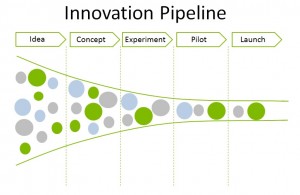

A first step should review your organization’s mission, vision and values. These elements will be important factors when weighting out which initiatives you will focus on and which priority of sequence. One of the next tools that I encourage organizations to consider is building a frame work for an Innovation Pipeline. The stages of a pipeline can be unique for the organization but should have a sequence of filters and gates that will help guide the team in making decisions and tracking ideas as they move toward execution.

An example that I use with retail organizations has five phases to a pipeline: 1) idea, 2) concept, 3) experiment, 4) pilot, and 5) launch.

An Innovation Pipeline as a tool

The pipeline moves from left to right. Ideas should enter the funnel and be captured from all of the stakeholder groups previously mentioned. The next step requires support from a group that can continually help compare and contrast those ideas against the mission, vision, and values. The ideas that rank well should be prioritized and move into concept phase. During the concept phase there will need to be some effort put to quantifying the idea. Ideas should be measured for their potential impact, possible drain on resources, likelihood of success, impact of not taking action, and risk to the organization. The goal is not to be 100% accurate with your calculations but with a degree of uncertainty that you and the organization are comfortable with.

The pipeline moves from left to right. Ideas should enter the funnel and be captured from all of the stakeholder groups previously mentioned. The next step requires support from a group that can continually help compare and contrast those ideas against the mission, vision, and values. The ideas that rank well should be prioritized and move into concept phase. During the concept phase there will need to be some effort put to quantifying the idea. Ideas should be measured for their potential impact, possible drain on resources, likelihood of success, impact of not taking action, and risk to the organization. The goal is not to be 100% accurate with your calculations but with a degree of uncertainty that you and the organization are comfortable with.

This is a good place to discuss the unique difference between Incremental vs Disruptive innovation initiatives. Incremental initiatives usually involve less unknown elements. They take an original product or service and build on it or change it slightly. With less unknown elements there is a lower risk of failure when launching the initiative. These ideas can more easily be tested and corrections can be made along the way. Disruptive innovation usually involves a higher degree of unknown elements and thus a higher risk of failure.

One way to reduce the risk of failure in either type of innovation is by running the concepts through an experiment phase. Is it possible to validate the hypothesis in a smaller test prior to committing the full amount of resources that would be required to launch such an initiative? The experimentation phase should be iterative – testing and retesting different variations of the hypothesis.

Once you have found pieces that work through the experimentation phase you can bring them together in a pilot program where you are testing something that will more closely resemble the final product or service. Similarly, the pilot phase is also an iterative process and sometimes will require running new experiments. A pilot is meant to give you “real world” feedback on your initiative before you roll out the final version.

The process culminates with the Launch (or Scale) phase. A couple of noteworthy points here based on experience and research – most ideas will not make it to the launch phase. According to a Fahrenheit 212 (a NYC based innovation consultancy) survey of 100 Chief Innovation Officers fewer than 25% of their innovation initiatives ever see the light of day. Most new ideas do not work out along the way. This is the simple reality of innovation work – new ideas require a level of risk taking. How much risk your organization can take or should take depends greatly on the organization. An example I often give is that most grocery stores operate on 3% gross margins and 1% net margins. Those thin margins leave grocers with very little room for error when trying out new ideas with their business. The good news is that they can run experiments easily with real customers every day and unlike social service nonprofits a failed experiment is not going to negatively impact someone’s life. If their failures can be quick and cheap they can minimize their impact.

Not perfection but a process

The intent of the Innovation Pipeline is not perfection but as a tool to help you manage the processes involved, develop criteria and measurement standards, funnel resources to priority projects, halt or end non-priority projects, and to reinforce an iterative process. Getting a project from idea to experiment is a success. Deciding not to go forward based on experiment results does not mean failure. Instead it means successfully freeing up those resources to work on another higher priority project. Maybe circumstances will change to your favor in the future and suggest that you retry that initiative but you cannot spread your resources too thin or you’ll be certain to find an abundance of failure.

Food for thought:

(image source: Huffington Post)

On Sunday morning three high school students were anxiously waiting for their science experiment to be lifted into orbit on board a SpaceX rocket that was scheduled to deliver supplies to the International Space Station (ISS). The students had been waiting for this day for eight months. Eight months ago the same students from North Charleston, South Carolina had watched as their experiment was launched on board an Antares rocket from Wallops Island, Virginia. Just a few seconds after liftoff the rocket had exploded knocking one of the students off of his feet and giving off a tremendous blast of heat. This time would be different. Surely lightning wouldn’t strike twice?

In this photo provided by Kellye Voigt, from left, Gabe Voigt, Joe Garvey and Rachel Lindbergh pose for a photo outside the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Sunday, June 28, 2015. (Kellye Voigt via AP) MANDATORY CREDIT

This time the rocket took off from Cape Canaveral, Florida and as it achieved liftoff the teens began to high five each other with excitement. But as they headed to lunch their phones began to buzz with messages of condolence. This rocket too had exploded before it could reach orbit. With two attempts the teens had two failures. What were the odds?

The reality is that while rocket failures are not as common as they once were when we ushered in the space race – they are hardly rare. In fact this was the third failed rocket attempt to resupply the ISS. The other cargo ship had to be abandoned in April after the Russians had lost control of it. Now a fourth Russian cargo ship is scheduled to launch on July 3rd as each of the other organizations continue to determine what had gone wrong.

What I really appreciated about this story was the reaction from the students, there are some real lessons in their comments for all of us.

Joseph Garvey noted that “this one didn’t hit as hard or hurt as much, maybe because they really didn’t see it.” Likely what also was a factor was that in feeling the failure of the first failure their anxiety was diminished with the second. They had already been through a similar experience, they survived and moved on.

Rachel Lindbergh said, “That’s rocket science. Failure happens.” She went on to comment, “Disappointing, sure, but you can’t let things stop you.” How many times have we heard someone use the phrase “How hard can it be… it’s not rocket science?” Well in this case it is rocket science. It is hard and there are lots of variables involved in these equations. Not even our most sophisticated computers can calculate every value and simulate the outcome. But we persist anyway. Sometimes we will fail and sometimes we will fail repeatedly. But as Rachel suggests – you can’t let things stop you.

Each one of these students shared a real maturity about the episode but Gabe Voigt had already recognized the value in this lesson. “There’s a lot of life lessons to take from this too.” He went on to suggest that “If something happens, that doesn’t mean it’s the end of that.” A failure can only be define as a failure when it is time boxed – otherwise it is just another attempt.

I have no doubt that these teenagers have the right attitude and hopefully their next attempt is successful. Either way they have successfully learned the underlying lesson of scientific discovery, innovation, entrepreneurship. Failures will happen along the way but as Albert Einstein noted “You never fail until you stop trying.”

Image Credit: Kellye Voigt via AP

We often hear about the importance of failure when driving new ideas or new businesses. We’re given advice to Fail Early, Fail Often, and Fail Cheap. While this well-meaning advice is accurate on the whole the reality is that failure in most organizations comes with pretty heavy consequences. Within mature organizations a failed initiative can have a dramatic impact for both the individual and the long term success of organization itself.

This post is from an article that I originally published on April 1st, 2015 in Innovation Excellence.

Until the last few years not much has been published about innovation failure rates within organizations because everyone feared the stigma or repercussions that came with disclosing any failure. For publicly traded companies the idea of giving stock analysts any ammunition for a critical stock rating would be tantamount to committing career suicide. Instead most organizations would prefer to quickly sweep their failed initiatives under the proverbial rug and hope they are never discussed again.

Until the last few years not much has been published about innovation failure rates within organizations because everyone feared the stigma or repercussions that came with disclosing any failure. For publicly traded companies the idea of giving stock analysts any ammunition for a critical stock rating would be tantamount to committing career suicide. Instead most organizations would prefer to quickly sweep their failed initiatives under the proverbial rug and hope they are never discussed again.

A couple of data points can go a long way in helping us to understand the frequency of innovation failure. It is first worth noting that there are significant differences in the success/failure rates of 1) incremental innovation and 2) disruptive innovation.

Incremental innovation is most commonly thought of as product line extensions (e.g. new cereal flavors, new soda brands, etc.) which tend to have lower failure rates. Incremental innovation can more easily be tested with consumers because there is a benchmark to compare and contrast against. Disruptive innovation is frequently a new to market product, service, or business model (e.g. Apple iPhone, Uber, HP Touchpad, etc.) that is much more difficult to evaluate prior to launch. With that increase in uncertainty comes a higher rate of failure.

Data scientist Thomas Thurston (@thurstont) is CEO of the strategic consulting firm Growth Science. For years Thurston has been working with innovative startups, large corporations, and educators trying to better understand innovation success by studying failure. Over that time he has amassed a significant data set of over 1000 corporate innovation initiatives. In the data Thurston has found that 78% of those initiatives cease to exist seven to ten years after their initial funding. Stated differently, 3 out of 4 of those initiatives either failed to reach scale or to become self-sustaining. Many others in the industry hint that the 78% sounds accurate with their experiences.

Even world-class innovation organizations see a significant percentage of failed initiatives. Last year I had a discussion on this topic with Mark Payne (@MarkF212) the President and Co-Founder of innovation consulting firm Fahrenheit 212. At the time Mark was proactively trying to address the issue of innovation failure by sharing the lessons he and his firm had learned in a book How to Kill a Unicorn. Mark noted that even with all of the experience that his firm brings to an engagement they see a 20-40% failure rate for innovation initiatives. Earlier in 2014 Fahrenheit 212 conducted an informal survey of 100 Chief Innovation Officers asking “what percentage of their innovation initiatives made it to made it to market?” What they heard back was that two thirds of the respondents saw a 75% failure rate or three out of four of their innovation initiatives never made it to market.

When leaders don’t recognize these high failure rates and the corresponding risks involved to their individual employees they are setting their organizations up for difficult consequences when innovation projects do fail.

In a previous article for Innovation Excellence (Five Ways Organizations Lose When They Cover Up Innovation Failures) I highlighted some of these consequences:

Based on these high failure rates and the negative impact to employees many in the innovation community have suggested it is better to just outsource their breakthrough (e.g. disruptive) innovation work to external teams.

If something sparks from that work then the internal team can focus on building out the necessary capabilities to sustain the innovation initiative. But if the project fails there is less impact to the organization. Simply stated the resources can more easily be eliminated if the initiative fails.

I recently co-hosted a Twitter Chat (#InnoChat) focused on the innovation domain where I posed the question of “Should mature organizations hire external teams or leverage internal resources if they want to drive breakthrough innovation?” The participants provided some great insights and direction to this thinking.

This is just a portion of the insights gleaned from the #InnoChat discussion but it is a great example of the “wisdom of crowds” in action. Everyone brought their unique experiences, priorities and perspective to the conversation making it a robust exchange. Here is a link to the complete transcript including insights into how organizations can help their employees de-risk their decision to join internal innovation initiatives.

While we still have an “it depends” answer I believe that the group has identified four great criteria that can help any organization through the process of determining their innovation resourcing strategy.

image credit: alleywatch.com

We are excited to announce a truly unique one day conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota – The Phoenix Rising Event! A day focused on strengthening our local community of entrepreneurs and innovators by addressing the fear, stigma, and shame of failure head on. Please mark your calendars and join us on Wednesday, May 20th, 2015.

Making mistakes is inevitable in life. But for entrepreneurs and innovators the path to success is always laden with frequent failures along the way. This conference is designed to help us navigate through those rough waters.

Making mistakes is inevitable in life. But for entrepreneurs and innovators the path to success is always laden with frequent failures along the way. This conference is designed to help us navigate through those rough waters.

In Greek mythology the Phoenix is a long-lived bird that is cyclically reborn. Quite frequently in entrepreneurship and innovation the individual that is able to rise from the ashes of their previous failures ultimately finds success. But rebirth can only occur when the individual demonstrates the resilience to stand again and the community around them supports their effort. We hope that The Phoenix Rising Event can help us in building that resilience and in creating that supportive community.

The event will feature over a dozen inspiring and insightful presenters from our Minnesota entrepreneur and innovation community. Each speaker will share their authentic experience with failure, their lessons learned, and their advice for moving forward.

Since risk, innovation, and failure are not unique to the for-profit world we have also intentionally included speakers from both the for-profit and non-profit communities.

In 2013, I had the chance to speak at the FailCon conference in San Francisco, CA. The conference was an eye-opener for me in just how far that community had come in building a healthy approach to risk and failure. They facilitated that journey by creating an open dialog around it.

Our goal with The Phoenix Rising Event is to strengthen our local community of entrepreneurs and innovators by tackling our collective fear of failure head on and by creating our own open dialog around it.

Please join us on May 20th for our first Phoenix Rising Event:

Wednesday, May 20th, 2015

9:00 AM – 4:30 PM

Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota

More information on our speakers and a registration link for the event are available via our website at www.phoenixrisingevent.com.

Yesterday Target Corporation announced that it was closing its 133 Canadian stores. This announcement comes less than two years after they launched their first Canadian stores in March 2013. According to Target CEO Brian Cornell the decision came down to the fact that it would take six more years before they would see a profit on their Target Canada subsidiary.

[This post was originally published on January 16th, 2015 via LinkedIn.com]

I first mentioned the challenge Target was having with their Canadian stores in a post from January 2013 (see Target Misses the Mark). At the time Target was delayed in launching their new Canadian stores and they had just admitted their failed partnership with Neiman Marcus. In that failed endeavor both retailers utilized high-end designers to create a unique collection of holiday gifts that both companies would sell online and in-store. Sales of the unique product never materialized and quickly those items were slashed to 70% off on their website with only a few being listed as sold out.

I first mentioned the challenge Target was having with their Canadian stores in a post from January 2013 (see Target Misses the Mark). At the time Target was delayed in launching their new Canadian stores and they had just admitted their failed partnership with Neiman Marcus. In that failed endeavor both retailers utilized high-end designers to create a unique collection of holiday gifts that both companies would sell online and in-store. Sales of the unique product never materialized and quickly those items were slashed to 70% off on their website with only a few being listed as sold out.

My suggestion to Target at the time was that they should examine what really happened with the failed experiment by taking the time to reflect on their story and being transparent within the organization. The goal would be to share 1) what had they accomplished, 2) what had they learned, and 3) what would they have done different. Going through this process would be a great chance for Target leaders to shape how the organization would handle risk and failure in the future. At the time they were still two months from opening their first Target stores in Canada.

When I speak on the subject of risk and failure I start by focusing on the distinction between mistakes and failures. Mistake can be caused by bad judgment, lack of information, or lack of attention to detail. We make numerous mistakes every day of our lives without serious consequence. While we would prefer to avoid mistakes we understand that without perfect attention and perfect prediction they are inevitable. Failure is a little different. Failure is simply a lack of success-when something you’re trying to accomplish fell short of what was required or projected. From the analysis on Target that I’ve read it sounds like they had made a series of mistakes that ultimately ended failure.

Pricing: From reports it sounds as if Canadian consumers loved visiting target in the United States. For many it was a good shopping experience and Target offered lower prices than they could find in Canada. But setting up operations in Canada increased costs and required Target to raise prices in their new stores. No longer did they have a pricing advantage over other Canadian retailers.

Experience: Another complaint from Canadian consumers was the availability of products. It sounds like Target stores were challenged to keep products on the shelves. Since they cited that sales were low this must have been problems with their operations of logistics capabilities. The other option is that Target over estimated their sales projections and didn’t want to burden their stores with higher inventory costs. Preferring instead to keep their shelves thinly stocked.

Loyalty: Another insight was that many Canadian consumers loved shopping Target when they visited the US but Target had failed to understand that they didn’t shop the same way as American consumers. They were also facing an uphill loyalty battle with Walmart and Canada’s Loblaws. This reminds be a bit of the battle that Coke faced with their loyalists when launching New Coke (see Creating Common Language).

The reality is that Target is not the first retailer to fail with their international expansion plans. In fact, the “king of retail” Walmart has had very mixed results. They have had success in the United Kingdom, South America, and China but failed in Germany and South Korea. Best Buy, another retailer located just minutes from Target’s headquarters, has had its own string of failed international expansions including China, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Just last month Best Buy announced that it was selling its Chinese retail brand Five Star to a Chinese real estate group leaving them with operations only in the US, Mexico, and Canada.

I am sure this failure will sting for some time for Target employees and their leadership team. If they ever again have an appetite for international expansion plans the question won’t be if they will see more failure but when they will see more failure. This work is inherently risky and the path is littered with previous failures. But how Target responds now will set the tone for how employees will perceive risk for years to come.

Food for thought:

Others articles on Target Canada:

Image Source: Huffington Post / The Canadian Press

Is your organization struggling to drive new innovation initiatives? The culprit may be that your employees are too afraid to fail. When talking with organizations I often hear the same refrain – we want our people to innovate but they won’t step forward to lead new innovation initiatives. Earlier this year I consulted with a company that was struggling with the same problem. The organization had been around for over 25 years and just a couple of years earlier a new CEO was brought in from Silicon Valley. The new CEO saw a lot of potential within the organization but too much of that potential was locked up behind department silos or trapped in the mindset of how things had always been done. He wanted his people to be free to innovate and drive the next wave of ideas and opportunity for the organization but after two years he wasn’t seeing the results he had hoped for.

When he recognized that his people were not stepping forward with their ideas or their support of innovation initiatives he asked his leadership team to help solve for “why?” This article is an examination of what was going on within the organization and some simple suggestions for both leaders and employees who might be facing similar circumstances.

When he recognized that his people were not stepping forward with their ideas or their support of innovation initiatives he asked his leadership team to help solve for “why?” This article is an examination of what was going on within the organization and some simple suggestions for both leaders and employees who might be facing similar circumstances.

Saying All of the Right Things

As I had mentioned the company has been in existence for over 25 years but for the first 23 years there was a hierarchical top-down approach to leadership. Research and development was done exclusively within a certain group and “innovation” was something that other departments didn’t really need to concern themselves with.

For most of the organization’s history this top-down hierarchical structure had been the accepted model and truthfully they had been reasonably successful with it. The company had successful innovations, their customers were reasonably satisfied and employees had chosen to remain with the company – for the most part.

The new CEO, having come from a large Silicon Valley company, quickly spotted a couple of the challenges facing his organization. There was a lack of synergy between the organization’s structural silos and there was lack of engagement from the employees outside of the research & development function. The new CEO saw great potential in breaking down those barriers and encouraging all employees to help drive innovation.

In response a new vice president was hired to lead the newly created innovation office and town hall meetings were held to encourage innovation across the organization. But still little innovation happened outside of the traditional R&D function. Sometime later at a follow up meeting with employees the company’s leaders asked “why they weren’t engaged in supporting new innovation initiatives?” The answer back from employees was that leadership was saying all of the right things but employees didn’t believe them. Employees had previously experienced the negative consequences from failed initiatives and they didn’t see how that policy had changed much.

The Organization’s Culture Hadn’t Changed

There’s an old adage that states “just because you keep saying it doesn’t make it so.” Most human capital (formerly human resources) and change management professionals will tell you that it takes significant rigor and years to effectively change an organization’s culture. The reality was that the company wanted employees to take on more risk but leadership hadn’t yet demonstrated how they would respond to failure.

Employees knew that these innovation initiatives were higher risk than their normal responsibilities. They had seen before how a failed project could threaten their earnings, their ability for promotion, and even their future employment. Before taking on these risks they would need to trust that their leaders were looking out for their best interest.

For innovation to thrive there would need to be a demonstrated shift in the organization’s culture. Employees would need to see that they weren’t punished for taking on these riskier initiatives. To be clear, I am not suggesting a “free pass” for employees who lead innovation initiatives but instead for everyone to understand and support that these are riskier projects.

The Risk vs. Reward Equation Was Out of Balance

The problems this organization encountered is not unique. Too often in business, just as in our personal lives, our actions don’t align perfectly with our words. In fact I recently met with a “world class” innovative organization who still struggles with the challenges of risk vs. reward. They have employees with 20 or 30 years of tenure with the company who are not willing to take on risky initiatives because it might tarnish their career and cost them that next promotion.

Here are a few recommendations I have for organizations that are struggling to build a culture of innovation within their organizations.

Innovative organizations are not born they are made and the same is true for innovative employees. Some employees are more adapt than others at creativity, risk taking, and moving ideas forward but without the right culture they too will soon sink.

Creating a culture of innovation where employees both trust and are trusted in innovative risk taking does not happen overnight. It happens when leaders are humble enough to listen to their employees concerns, to make the investment and changes necessary to change the culture, and to reinforce the necessary behaviors with their own actions.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and feedback. If you found it valuable please feel free to share it.

If you are interested in learning more about creating a culture of innovation here are some other articles worth reading:

When Failure Is Your Starting Point There Is Nowhere to Go but Up. Are you the type of person that’s always looking for a good challenge? Here’s one for you to consider: We want you to provide financial literacy and entrepreneurial training to one of the poorest communities in your state. In fact, it’s also one of the poorest communities in the nation. The community of nearly 9,000 people doesn’t own land for homes or businesses. In many instances the people there have no credit score. Less than 1 percent of the businesses in the community are owned by a community member, and more than 47 percent of the jobs in the community are not in the private sector, but are government-related. Are you up for the challenge? It’s exactly what Tanya Fiddler took on when she became executive director of the Four Bands Community Fund, which serves the members of the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation.

The Four Bands Community Fund was started in 2000 as resource for financial literacy training, entrepreneurship education, and small business training and lending. To date the fund has lent out more than $8 million in cumulative deployment to its community. The people there are building credit and the community is growing because Tanya Fiddler accepted the challenge. She wasn’t satisfied with the status quo and wanted to make both herself and the community stronger through financial independence. This is her story.

The Four Bands Community Fund was started in 2000 as resource for financial literacy training, entrepreneurship education, and small business training and lending. To date the fund has lent out more than $8 million in cumulative deployment to its community. The people there are building credit and the community is growing because Tanya Fiddler accepted the challenge. She wasn’t satisfied with the status quo and wanted to make both herself and the community stronger through financial independence. This is her story.

[This article was originally published in Pollen on October 23, 2014]

Q1. Many of us are not familiar with the challenges of building financial literacy programs on a reservation. Can you share some of the hurdles that you faced starting out – including public versus private sector jobs, banking, and property ownership?

It is important to know that according to a CFED report, 55 percent of our tribal population is unbanked and/or under-banked (see map – the reservation spans Dewey and Ziebach Counties in South Dakota). Most have very limited experience with banking. Our tribe is federally recognized and has “sovereign nation” status. The nation owns and controls most native-owned land/assets and tribal members can get a “lease assignment” for business or homeownership purposes. In addition we can also get tribal range unit leases for native-owned ranchers. Having no land assets or property complicates the collateralization required to access financial products for loans or credit. So although you build a home on your five-acre land lease assignment, there is no value on the land or property. This also means that property taxes aren’t collected. Often that money is what sovereign states use for infrastructure development and maintenance.

When Four Bands started the reservation population was 80 percent Native American, however they owned less than 1 percent of the businesses. This was the major driving factor for our loan fund. We wanted to increase access to capital, provide business training and technical assistance, and support native business incubation.

We knew many of a tribal members lacked personal and business financials skills. Since our inception we have trained thousands of tribal members in these skills, along with bookkeeping, marketing, and other specialized courses. Knowing that our market had this low skill level going in, we tied all of our financial products to a training or technical assistance requirement. So far this work has resulted in over $8 million in loan capital deployed in two of the poorest counties in America. We say in our work that we are “creating our economy” because of the lack of historical investment in private sector development and job creation.

Job creation presents another unique hurdle in our community, as evidenced by the disproportionate number of government jobs provided on “the rez” (reservation). Our research shows that 47 percent of the jobs on Cheyenne River are government jobs, compared to 15 percent statewide and just 14 percent nationally. We needed more jobs in the private sector in order to create a more stable economy, circulate dollars locally, and decrease our dependency on the tribe and the federal government for jobs.

Q2. We know that many of us learn best from example. As you launched the Four Bands Community fund, how difficult was it for these communities to identify “examples of good” in financial literacy to learn from?

It was extremely difficult. We were trying to expand the financial education work in many ways, but because of the huge need for it we knew that we were going to have to identify partners and systems that could help us leverage our limited resources. Originally we thought we could leverage many of our Tribal Program Service providers who already work with our low-income, distressed community members. Since these providers already work with the same group we hoped to reach, we tried partnering with them.

We hired a financial skills trainer to deliver a “train-the-trainer” session for our Building Native Communities – Financial Skills for Families program. We thought since these providers were jobholders, they would have a general idea of money management and credit. We set out to create a delivery system supported by one trainer and 36 service providers that had gone through the training. This leverage would quickly increase the number of tribal members that could get help and training.

But while the service providers graduated as certified trainers, none of them felt confident enough to help anyone else. It was eye opening to say the least, and we realized that we needed a new approach. From this failure we devised another strategy that eventually became our Making Waves Campaign.

Q3. You had mentioned that early on you tried to launch an after-school program to teach financial literacy that failed. Looking back, can you share the shortcomings of the program?

We started by going into the schools trying to operate an independent after-school program to teach financial literacy. We soon discovered that most of the 2,000 kids rode the bus and couldn’t stay after school. Those that could stay were often in sports so they couldn’t make the meetings. We realized we also lacked an internal champion within the school system itself. Teachers thought what we were doing was critical because of the high poverty on the reservation, but they were already overcommitted and couldn’t take on additional after-school duties.

That’s when we figured out that we needed to meet the students and teachers where they were at by integrating the concepts into the core subjects that were already being taught. Hence the Making Waves K-12 Teacher Toolkit was created and tested. There have been many other challenges in our delivery model, but we have trained several other tribes and tribal programs on how to service the delivery model we created.

Q4. When you began your work you mentioned that there were systemic failures that prevented your communities from finding success. One of those failures was a lack of credit reporting on the reservation. Can you explain how your group is working to resolve that shortcoming?

We had three banks in the local community and none of them reported their lending to credit bureaus. We were told that their attorneys advised against it because of all of the regulations and potential lawsuits that might come from any inaccurate credit reporting. This was a huge barrier in a low-income community because its individuals have no credit score. Those that are in successful repayment of a loan cannot show that they are creditworthy to other lenders for personal loans or business loans. With no credit score, our members are vulnerable to predatory lenders because no one else will lend to them. There is an exorbitant number of payday, predatory, or title loan companies that are actively advertising on the reservation.

We were new in the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) industry, but were networking and learning from other microenterprise development organizations both rural and native to try and find a solution to the problem.

Finally, our advocacy was heard and a national nonprofit called Credit Builders Alliance (CBA) formed and began to work with the credit bureaus to launch a plan to warehouse our loan repayments so they would hit one of the major bureaus. I think currently two of the three national credit reporting agencies receive our data.

When credit reporting became available we launched a credit building loan product. It was a short-term, low-cost loan to help people begin to build credit histories. We began with personal finance training, ordering the customer’s credit report, and then setting goals to build or rebuild their credit histories. We have a credit coach that helps members create an action plan to maintain good credit and have seen astonishing results. We had found that 55 percent of the folks coming in our door had no credit histories at all. Many of our clients went from no file, to building a score in the low 600s after the first year. Most that did have credit files had scores nearly 100 points below the national average of 700. The credit builder loan helped members clean up bad debt and rebuild their credit histories. The CBA evolved to create a system/service for “soft pull” of credit reports that didn’t impact credit inquiries on the customer credit file.

Q5. How much in community loans did you make your first year and how much has that grown since? Which organizations have been most supportive in helping that growth?

We did $19K in micro business loans our first year and broke the $1 million mark in 2008. In seven years we built a capacity for larger loans and new loan products. We expanded our lending seven times over the last six years, with a total cumulative deployment of more than $8 million to date.

Our growth can be contributed to our Making Waves Strategy that has been deployed through 12 community organizations to implement financial literacy and entrepreneurship behaviors. These partnership opportunities helped expand program outreach and gave us additional ideas for loan products and services. Our advocacy network, the South Dakota Indian Business Alliance, is the other organization that helped escalate our growth through statewide access to capital through the Native Entrepreneurship Investment Fund. We managed and grew that fund from an initial Citi Foundation investment of $100K, to $1.2 million in off-reservation lending.

Q6. You mentioned before that most of these financial concepts were foreign to you – having grown up in poverty yourself. How have you personally managed the steep learning curve you faced?

I am trying to serve tribal members that have a similar story to me.

I completed my first personal finance class after I got divorced and moved back to the reservation with my two kids. I worked as a loan officer for a housing nonprofit developer that was promoting homeownership using federal programs. I worked to get borrowers ready or prequalified for the lending programs. When I got divorced I had to file for bankruptcy and start from scratch. I got counseling from Consumer Credit Counseling of the Black Hills and later discovered its curriculum “Credit When Credit is Due.”

I took the course and I woke up. I didn’t have any previous financial education beyond that. Growing up it was embarrassing when your mom gives you a bad check to buy groceries while she’s traveling and trying to provide for six kids. There was always so much stress, shame, hurt, and anger in our world around money. I hadn’t seen anyone that was successful at it.

So after taking the course and working on my own personal finances, my experiences directly translated to many of the customers I had in housing and then later at Four Bands. It was a life changing moment when I began to pursue financial education. I rebuilt my finances after bankruptcy and put my kids through college.

Once I came out of income poverty I had to deal with asset poverty. I didn’t have assets to leverage for my kids’ education and they were no longer eligible for aid because of my income. Everything was an out-of-pocket expense. Only later in life did I develop financial skills and asset-building strategies. I just didn’t have ample time to create college funds for my kids.

This is why I think it’s important to have an Individual Development Account program where families can save and get matched for that initial investment into homeownership, business startups or higher education. Many outsiders assume these assets are readily available, but that’s not the case in reservation communities. Without a community development organization to provide the initial investment in that person, things such as a home, business, or college education are out of reach.

Last year I lost my husband so retirement planning has taken on a whole new meaning for me. Luckily my kids have all completed personal finance training, have great credit histories, and are now coaching me on how to plan for my future. My son has even become my financial advisor. I feel like we have broken the cycle.

Q7. What advice do you have for other leaders who want to make a difference in their communities but are facing similarly difficult starting points?

Leaders, especially community leaders, need to see what’s right about the place instead of everything that’s wrong. Messaging and the media in Indian Country are usually negative and frequently cite everything that is wrong. A good leader is able to look past that and identify the assets in the community to create products and services to meet people where they are at with dignity and respect.

You also have to be authentic and truthful about your own experiences. Talking about my financially reckless life gave other people the ease to talk about themselves.

I also discovered that for the most part, credit reports from our community were not as bad as people thought. Just the education alone helped people develop comfort and proficiency in having a discussion around credit. There is a lot of shame and suffering in low-income households, so we focus on providing a supportive environment to eliminate that shaming. We have countless examples of how our customers benefited and saved themselves from financial woes because of the education they’ve received.

Q8. If Pollen readers want to offer a helping hand in your work, what’s the best way to get involved?

We collect a lot of information that we could use help analyzing. Folks can invest in our loan fund to keep the work rolling. That info is available on our website: www.fourbands.org.

I would also encourage readers to come and visit Cheyenne River for hands-on learning about the realities on our reservation – both good and bad. We have some people who think we still live in teepees, and others who are afraid to drive through the reservation because of news reports on violence. We invite people into the community so that can help us debunk these myths and help us make connections with the outside world that may benefit our work.

Finally, if readers are considering expanding a business, give us a chance at the opportunity. Our CDFI is innovative and resourceful, with keen expertise in successful community economic development.

Tanya and the Four Bands Community Fund have undoubtedly made great progress, but they will tell you that there is still much to be done to improve the lives of people in their community. Their first attempt to teach financial literacy in an afterschool program failed, but it was a move in the right direction. Tanya and the team knew it was going to be a challenging journey and that they would make mistakes along the way, but they were willing to pick up the pieces and try again. If not for the lessons learned, they might not have found success with their revised Making Waves program. You can read more success stories from the community on their website at http://fourbands.org/success.htm.

If you are interested in connecting with Tanya or learning more about her journey, you can reach her via LinkedIn and email at tfiddler@fourbands.org, or you can stop by the reservation for a visit.

Receive periodic email updates from Matt Hunt including his published pieces, updates on his progress, and more!